As a therapist, I get to witness a lot of New Year’s Resolution mistakes first hand.

In this article, I’ll briefly describe three of the most common psychological pitfalls people tend to fall into when setting and working on their New Year’s resolutions and goals more generally.

If you can learn to see and avoid just these three mistakes, you’ll be far more likely to succeed with your goals and resolutions in the long-term.

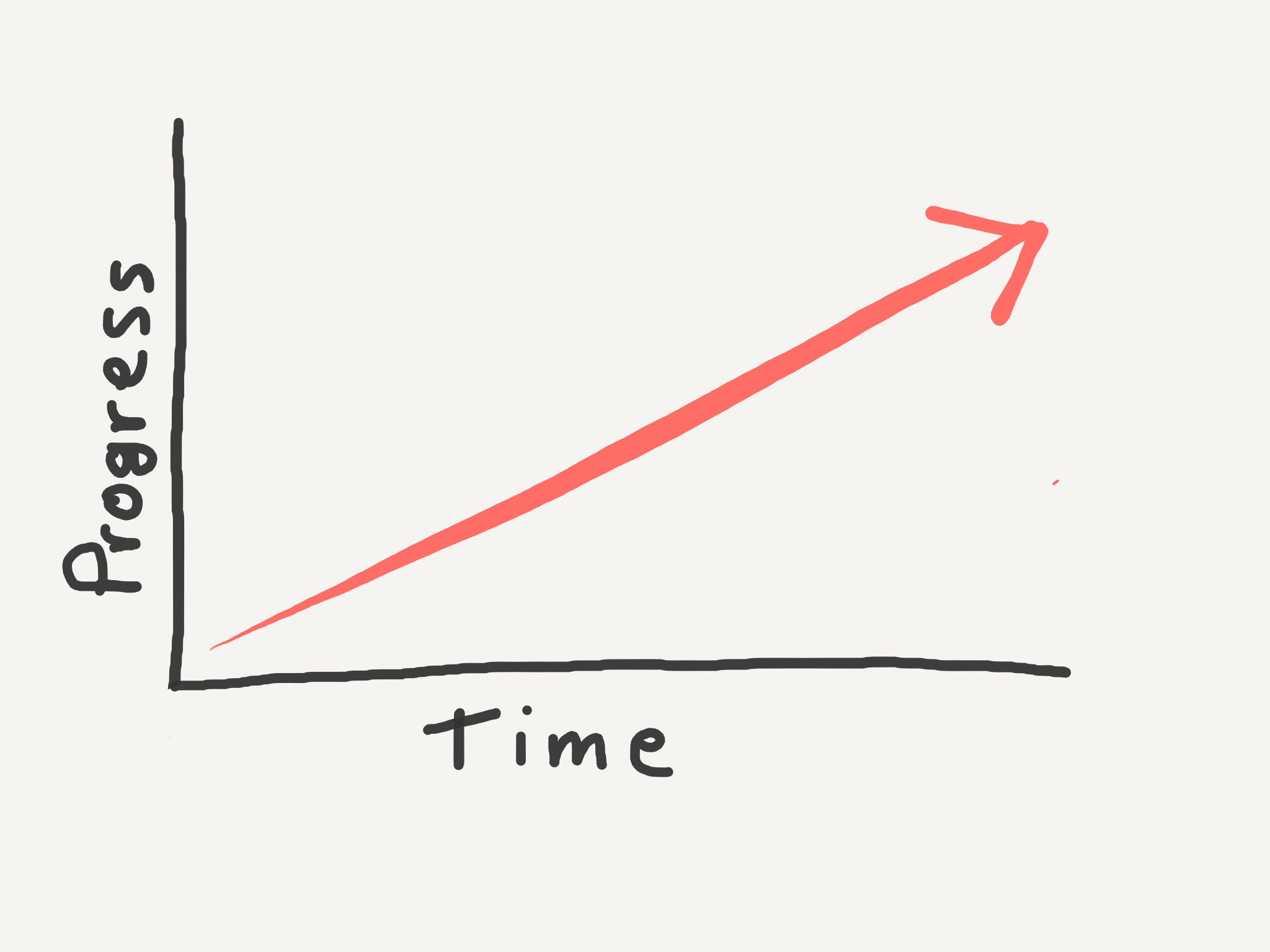

Mistake #1: We’re not very good at reminding ourselves of what progress really looks like.

Most of us tend to think of progress as a straight line:

But this is a cartoon, an idealized abstraction. And thinking about our new year’s resolutions and goals like this can actually cause us to fail at them.

When we routinely imagine that our progress should look like a straight line, and then compare our own less-than-ideal version with it, we are going to feel a lot of negative emotion (shame, embarrassment, fear, frustration, etc.) which will make it that much harder to persevere.

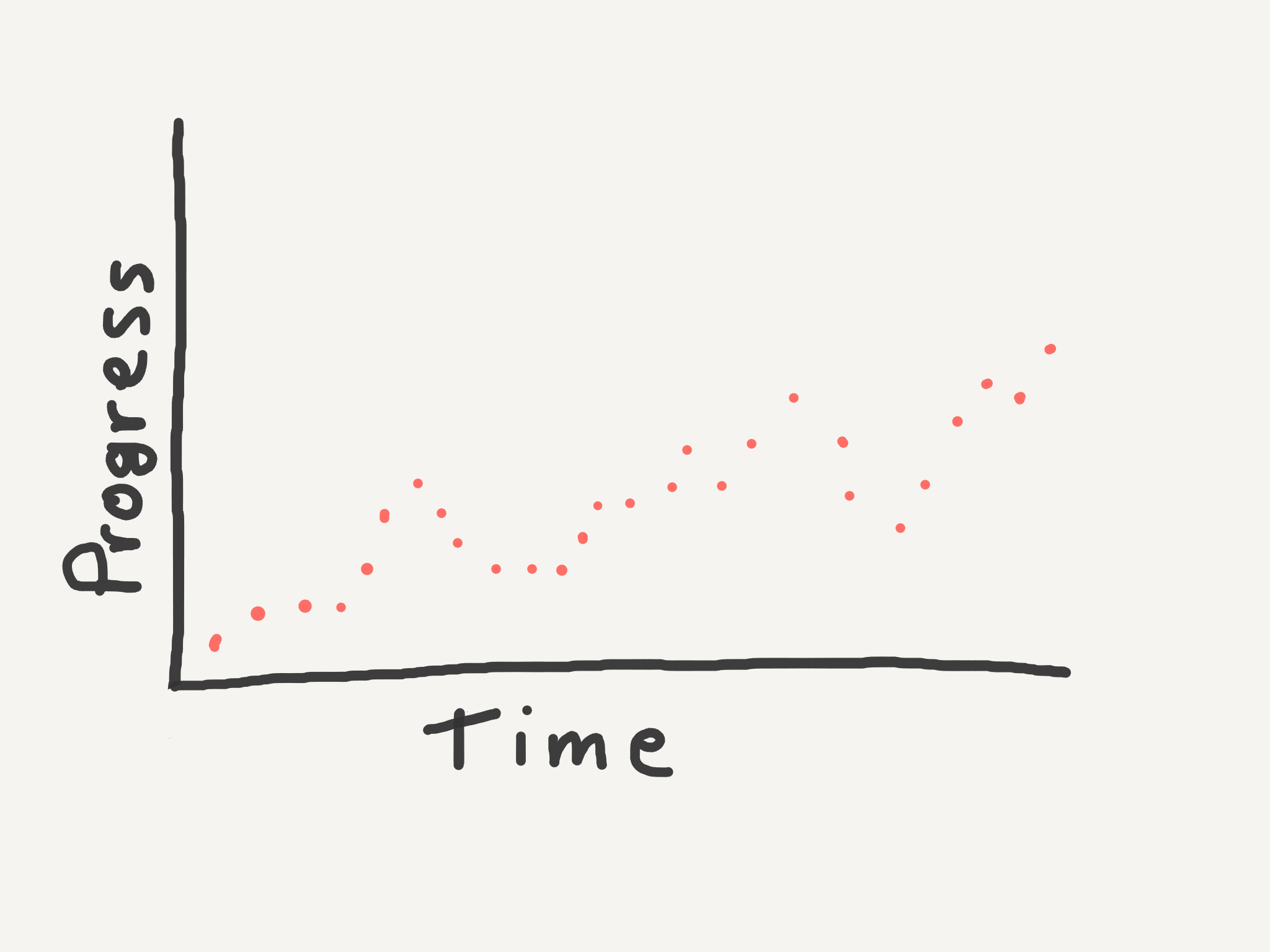

Instead, what if we got in the habit of looking at our progress a little more realistically and comparing it to a more realistic standard?

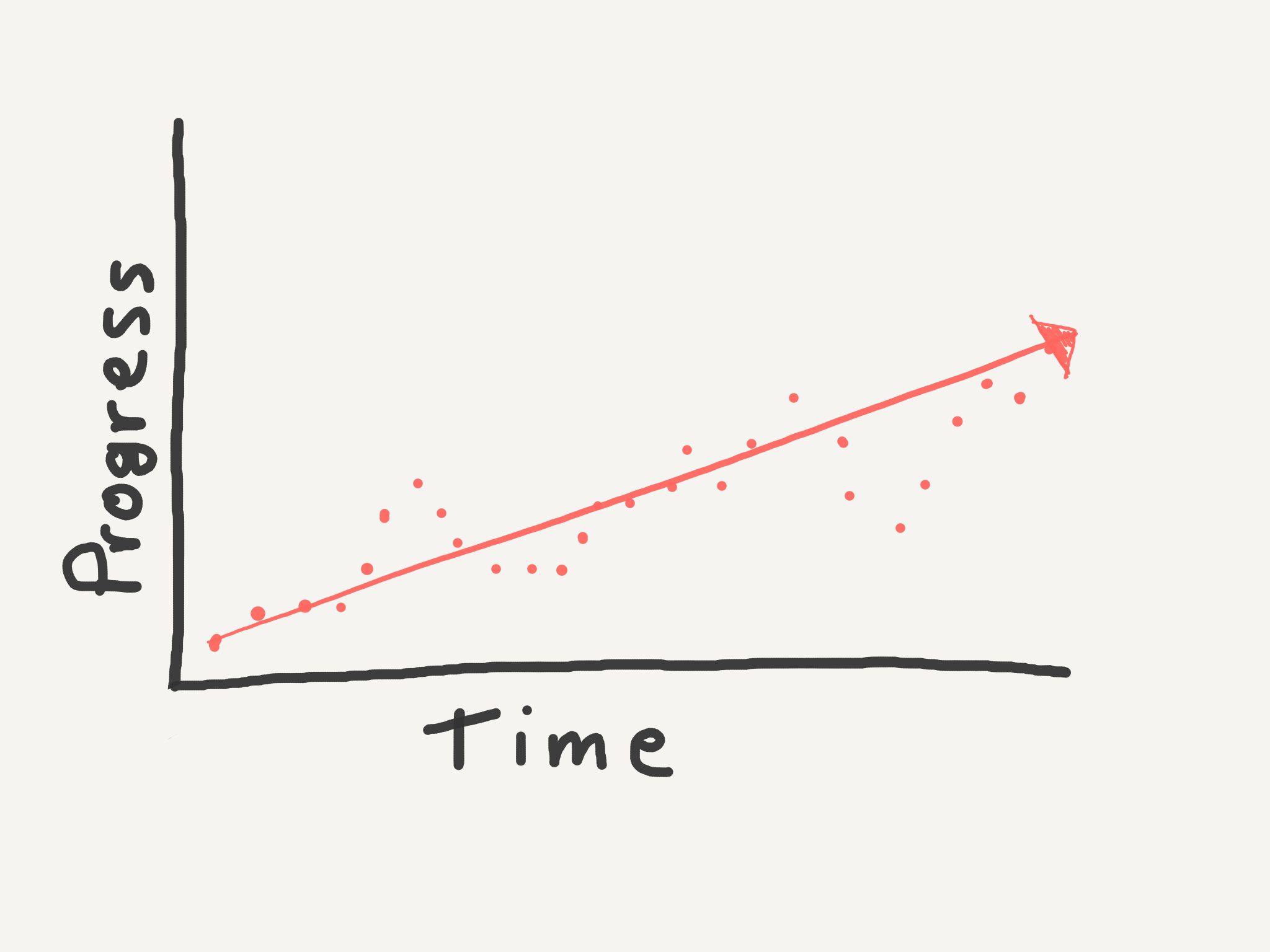

I think if we actually detailed what progress looks like for any significant endeavor—whether it’s losing weight, learning guitar, or saving for retirement—the picture probably looks closer to something like this:

In a word, it’s messy.

It’s important to get in the habit of reminding ourselves that progress is messy and avoid situations that reinforce the idea that progress is and should be linear and clean.

How to Practice:

One of the best things we can do to create a more realistic standard for progress is to spend more time reading biographies and having real conversations with people and less time on social media.

Good biographies, like good conversation, tend to paint realistic (i.e. messy) pictures of how people both failed and achieved progress.

Social media, on the other hand, is full of people showing off only the best, most idealized versions of themselves, which encourages our unhelpful habit of thinking our own progress should be nice and clean.

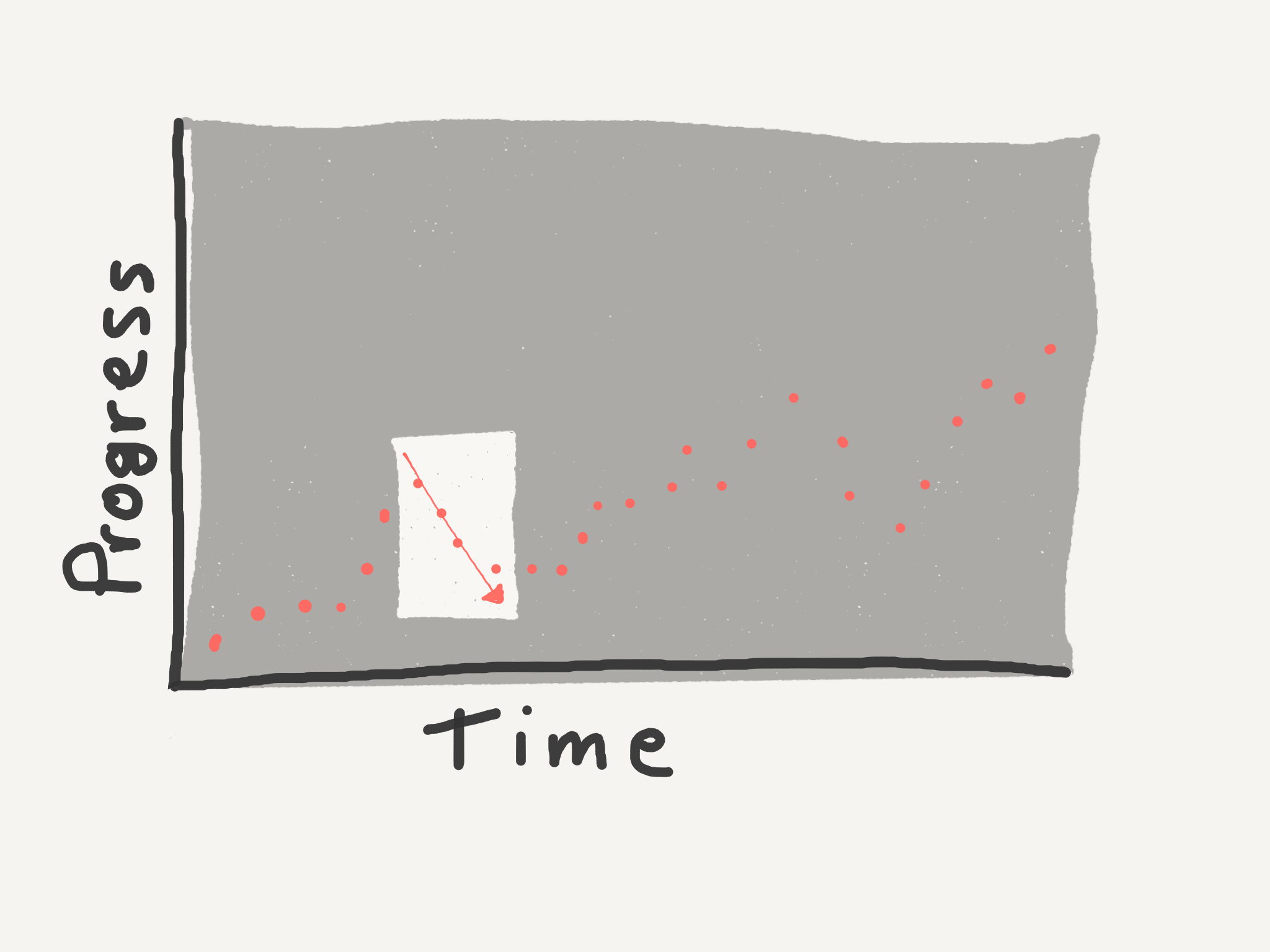

Mistake #2: We’re not very good at “zooming out” on our progress when we stumble.

A practical application that comes directly from learning to see the messy nature of progress more clearly is the art of zooming in and out on our progress.

While we’re working at something, it’s often good advice to keep our heads down and focus on the one or two tasks at hand or right in front of us. In other words, to stay zoomed in on our progress.

But, if we start struggling or fail to make significant progress for a while, this zoomed in perspective can make things look a lot worse than they really are:

Instead, we need to build the habit of zooming out on progress when we falter or stagnate, reminding ourselves that it’s normal to experience dips and plateaus, and that the overall trend line of our progress (which we can only see when our perspective is zoomed out) is a much better indicator of progress than a zoomed in one that uses only one or a small set of data points.

How to Practice

Get in the habit of meticulously tracking your progress.

There’s no way to actually zoom out on your progress if you’re not keeping track of it somehow.

If I had to single out one factor that consistently predicts people sticking with their goals, it would be having a reliable method for tracking progress. Personally, I like The Seinfeld Method.

Mistake #3: We confuse leading and lagging indicators of progress.

In economics, a leading indicator is an event or piece of information that signals or predicts future events. The number of filings for new building permits, for example, is often considered a leading indicator of a growing economy.

A lagging indicator, on the other hand, is an event or piece of information that follows or confirms a past event. The number of unemployment filings is often a lagging indicator that the economy is weakening.

It’s useful to apply the idea of leading and lagging indicators to progress in personal growth, but only if we do it correctly.

The first mistake I see most people make in this respect is that they use how we feel as a leading indicator of progress. Most commonly, they take feeling badly as evidence that they’re not making progress.

- We feel like a pig after a crushing a whole pint of Ben & Jerry’s—ashamed, angry, and bloated—which we take as evidence that we don’t have enough willpower to diet successfully.

- We’re certain that therapy must not be working because we got really anxious this weekend after having been anxiety-free for the past 3 months.

- We feel listless and lethargic sitting on the couch while contemplating getting dressed and going for a run, which we imagine means that we’re lazy and not really up for the project of running that half marathon.

Psychologists, by the way, call this emotional reasoning—using how we feel as evidence for the nature of ourselves, the world, or the future.

How we feel is almost always a lagging not leading indicator. Which brings us to the other mistake we make with indicators of progress…

While we often mistakenly think of feeling negatively as a leading indicator of a lack of progress, we also forget the flip side of that idea: That feeling positively is generally a lagging indicator of progress.

In other words, feeling good doesn’t usually happen before or during progress, it tends to happen after we’ve already started to make some progress.

- We feel more energetic and alert after a couple weeks of exercising regularly. But it’s unrealistic to expect that we’ll feel amazing and super energetic walking out of the gym after our very first workout in two years.

- We feel proud of ourselves after mastering that complicated guitar riff. But it’s unlikely that we’ll feel proud as soon as we start practicing it or immediately following our first attempt.

- We feel a little bit calmer throughout our days after a week-long meditation retreat. It’s hard to imagine, though, that you would feel an immediate sense of calm as you walk through the retreat center door—if anything you’d expect to feel a little nervous.

How to Practice

Before setting out on a new goal or resolution, spend 10 or 15 minutes deliberately thinking through genuine leading and lagging indicators of progress.

Come up with a list for each of the factors you think would realistically predict future progress and confirm past progress.

If you’re having trouble, ask someone you know who’s successfully achieved the same or a similar goal.

Summary and Key Points

There are three common mistakes we make with our goals and New Year’s resolutions:

- We’re not very good at reminding ourselves of what progress really looks like (It’s messy!).

- We’re not very good at “zooming out” on our progress when we stumble.

- We confuse leading and lagging indicators of progress.

To avoid these mistakes and increase your odds of sticking with your New Year’s resolutions and goals, remember to:

- Cultivate realistic standards of progress by reading biographies and having conversations with real people about their progress.

- Always track your progress meticulously so that you can zoom out when yous tumble and still see the bigger picture and trend lines.

- Make sure you’re clear with yourself before you begin a New Year’s resolution about what true leading and lagging indicators of progress are (hint: feeling good is probably not a leading indicator of progress in most endeavors).

Good Luck!