Occasionally my background as an English major bumps into my day job as a psychologist.

This morning I was listening to Henry Oliver interviewing Matt Yglesias about Matt’s recent experiment reading more classic literature. Toward the end of the discussion, Henry asked Matt what the tangible benefits have been of reading all these classic novels. Among other things, Matt said it’s made him calmer and less anxious.

As someone who loves literature—and helps people with anxiety for living—I was intrigued by the idea and spent the rest of my morning walk thinking about how reading good literature might be beneficial for anxiety.

I came up with three ideas…

1. Speed

Everything about anxiety is fast.

Just think about how frequently we use the metaphor of racing to describe anxiety: I tried to fall asleep but my mind was racing. I couldn’t stop worrying as thoughts raced through my head. My heart was racing as I stood backstage anxious before the big speech.

But it’s not just our minds and bodies that are racing—it’s the world we live in: the endless scroll of social media, BREAKING NEWS 24/7, the constant avalanche of Slack messages at work, ferrying kids back and forth between dozens of activities, all while trying to hurriedly squeeze in workouts, yard work, and all those self-care activities our therapists keep harping on about.

If we spend our days racing through an already fast-paced world is it all that surprising that our minds tend to race too?

It doesn’t seem crazy that anxiety is at least in part a natural consequence of choosing to live fast-paced lives. And if that’s true, I suppose slowing down a little ought to help us be less anxious.

Well, few things force you to slow down as much as reading a 600-page novel. Long-complex sentence structures nudge us to think and observe more slowly and more carefully. Multiple character arcs over branching plot lines encourage us to be patient. Even the simple act of reading a book forces us into that long-forgotten position of sitting still—without being plugged into a screen or headphone.

Of course, it’s a big claim that high-speed living causes anxiety—and that slowing down by reading a long novel might cause you to feel less anxious. In fact, they’re claims I would be naturally skeptical of if I heard someone else making them. Still, it’s a pretty simple experiment to run for yourself.

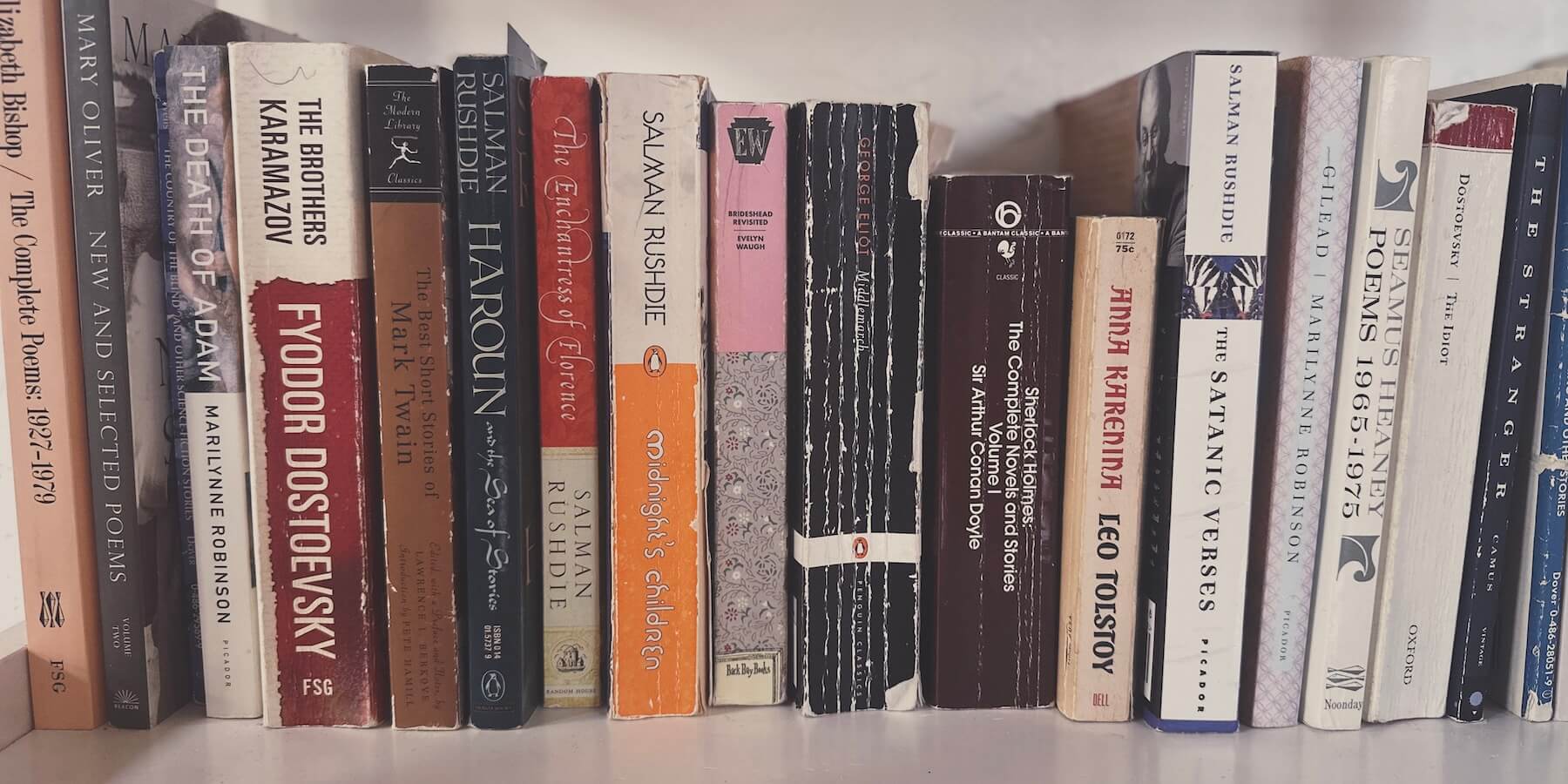

Like Matt, find a handful of classics you’ve always meant to read—or maybe old favorites you’d like to re-read—and see if an hour per day reading helps you feel a bit less frazzled and a bit more calm.

2. Connection

A common pattern I see in my work with anxious people is disconnection.

It’s hard to be present with your spouse as they describe what a tough day they had when you’re simultaneously worrying about how stressful your day is going to be tomorrow. It’s tough for your kids to feel connected to you at dinner time if you’re anxiously stewing over the implications of that new executive order you just read about on Twitter/X. And it’s hard to be present and empathetic with your client or patient if you’re stressing about that party you agreed to co-host with your sister-in-law this weekend.

But it’s not just disconnection from other people; anxiety disconnects us from ourselves. It’s tough to be attuned to your own emotions if you’re too anxious to acknowledge them. It’s hard to be mindful of your body if your knee jerk reaction to stress is overthinking. And it’s hard to know what you want—your values, goals, purpose—if most of your decisions are based on running away from what you don’t want instead of exploring what you might.

So, while anxiety can certainly cause disconnection, I think the causality goes the other way too. When we feel lonely in a relationship, we’re more vulnerable to worrying about it and feeling inadequate. When we feel lonely at work, it’s a lot easier to get lost in self-doubt and imposter syndrome. Even feeling lonely and disconnected from yourself (maybe because you’re so busy, you don’t have much time to spend quietly alone with yourself) can lead to a sense of insecurity and unhealthy dependency on others.

Of course, it might seem that sticking your nose in a book for an hour every day isn’t exactly an ideal strategy for becoming more connected. But talking out-loud with another person is hardly the only form of connection. We feel connected to loved ones who have passed away when we lose ourselves in a memory of them. We feel connected to God when we pray. We feel connected to younger versions of ourselves when we listen to an old song we’d forgotten about. There are many ways to connect and feel connected.

Reading good literature generates connection on at least three levels:

- You feel connected to the characters themselves. You can’t read Pride and Prejudice without feeling more connected to Elizabeth Bennet than you do most of the people you interact with throughout the day—grocery store clerks, Starbucks baristas, Instagram influencers, and the like. And if you’ve spend a lot of high-quality time with a specific novel, the connections you form with the characters can become profound: I’m on my fourth reading of Middlemarch and on multiple levels—intellectual, spiritual, emotional—the level of connection I feel with some of those characters is more nuanced and meaningful than many of the casual friendships and relationships I have in my “real” life.

- You feel more connected with yourself. Here’s a recent example from my reading of Middlemarch. Early in the book, one of the heroines, Dorothea, remarks: “People may really have in them some vocation which is not quite plain to themselves, may they not? They may seem idle and weak because they are growing. We should be very patient with each other, I think.” Impatience is one of my biggest struggles. But this sentiment—that patience isn’t just about tolerating something you don’t like, but instead, actively supporting another person in their growth and becoming—has been a powerful shift in how I go about my own attempts at growing into a more patient person. Specifically, it’s helped me to be more patient with myself when I’m feeling impatient of others. By relating to myself differently, I’m able to relate to others differently—all because of a connection—a meeting of minds—between myself and a fictional person.

- You feel more connected with humanity as a whole. We live in turbulent times. Whether it’s contentious political upheaval, rapid technological change, or seismic cultural shifts, it can definitely feel like, in the words of a friend, “people are the worst, everything’s going to shit, and we’re all screwed.” But spending just a little time with great works of literature—many of which are set across times and places far removed from our own—you realize that our current age isn’t all that special or unique in its tumultuousness. People have always done terrible things. Politics has always been messy and nasty. Societies and cultures have always been going through revolutions and upheavals. Humanity is a hot mess and always has been. There’s something oddly comforting in knowing that—and knowing it viscerally, the way you do when you’ve lived in a novel, not just read about it on Wikipedia.

3. Beauty

We’ve talked about how speed and disconnection make us vulnerable to anxiety, but what about ugliness—or at least, a lack of beauty?

I always get a little depressed and edgy walking into hotel rooms. Something about the generic paintings, taupe-colored walls, and overly-starched sheets is unnerving. Too much function, not enough form. Too much efficiency, not enough imperfection. Too much cleanliness, not enough personality. They’re nice, but ugly. And even when they try to be beautiful, it feels forced and inauthentic. I feel this ugliness emotionally, often in the form of a vague unease or mild anxiety.

Contrast that with walking into a well-loved home that’s quirky and a bit messy but undoubtedly reflects the character and charm of the people who live there. It’s shabby, but beautiful. Messy but cozy. Rough but beautiful.

It seems that in a lot of our lives we’ve made the decision to surround ourselves with objects and environments that are affordable, convenient, and ”nice,” but lacking in character, personality, and beauty. That’s not to say affordability and convenience are bad, of course. But perhaps we’ve swung a bit too far to one side of the pendulum? And maybe without knowing it one of the costs of this decision is that we’ve lost a kind of natural buffer against anxiety by reducing the amount of beauty we experience on a regular basis. Or, put another way: Is beauty a natural anxiolytic?

When I spend time walking through the forest, or staring into a campfire, or wandering through the halls of The Art Institute of Chicago on a quiet Wednesday morning, it sure feels like. The same goes for pouring warm maple syrup out of the hand-made ceramic cup a friend gifted me. Or wandering through the Spanish countryside with Don Quijote.

Outside of slowing us down and helping us connect, maybe reading great literature provides an escape into beauty which is inherently calming?

It could be the beauty of the physical world the book invites us into—think of the Greek ships of Homer’s Iliad sailing across the wine-dark sea toward Troy or the misty backstreets of Sherlock Holmes’s London. It could be the emotional beauty of how Dickens describes a certainty wrinkle in an old friend’s gaze or the intellectual beauty of one of Austin’s ironic barbs. It could even be the formal beauty of the book—Eliot’s long meandering sentences that flow river-like and settle us into a more contemplative and less judgmental mood.

To lose yourself in a great book is to surround yourself with layers of beauty. And it’s hard to believe all that beauty wouldn’t knock a few points off your blood pressure or mellow out your nervous system.

Read More

If you enjoyed this essay, here are a few more from me you might like: