Motivation is a complicated thing…

- Why do we feel energized and inspired by some goals but bored and anxious by others?

- Why do we start some projects enthusiastically only to “lose steam” partway through?

- Why do some people seem so passionate and driven while others seem listless and lost?

Over the years working as a psychologist, I’ve run into this problem a lot with my clients…

How can I be more motivated to… X?

Of course, everyone’s situation is different. And I certainly am not the world’s leading expert on the psychology of motivation.

But I have spent a lot of time “in the trenches” working with people to build more motivation into their lives. And as a result, I’ve found a few insights that I think are helpful for just about anyone who wants to become a little more motivated.

1. Think About Motivation as an Effect, not a Cause

If you’re reading this article, it’s probably because there’s some action or set of actions you would like to take, but you don’t feel as motivated as you would like to take them.

The underlying belief here is that you’re more likely to do the action if you possess the feeling of motivation.

True enough. All things being equal, it’s going to be easier to perform an action—especially a challenging one like going to the gym after a long day—when you feel motivated.

But the relationship between motivation and action is a two-way street:

Feeling motivated makes it easier to act, but acting also leads to feeling motivated.

The trouble is only one of these things is something you have direct control over… Sadly, there’s no “Feel More Motivated” button we can just press to get a boost of motivation. If you don’t happen to feel motivated, the only way to get there is to do things that lead to feeling motivated.

Stick with our going to the gym example, it’s usually about 50/50 whether or not I feel motivated to work out—half the time I do, half the time I don’t. But I can’t think of a single time when working out didn’t make me feel good—including more motivated to work out in the future.

Taking action is something we have direct control over; feeling motivated is not.

This means that spending too much time thinking about feeling motivated is going to be pretty unhelpful—especially if it distracts you from there one thing you can do to actually feel more motivated in the long run: act.

When you think about motivation as a cause—something you need in order to act—it tends to lead to discouragement, inaction, and less motivation. But when you think about motivation as an effect—something that you get as a result of action—it often leads to energy, confidence, and more motivation.

2. Sharpen Your Why

Your why is your reason for wanting to feel motivated and do something.

For example, if you want to start a new business, your why might be:

- To make more money

- To have more control over your time

- To impress your friends

- To fix a problem no one else sees

Now, we typically talk about our why with phrases like “What’s the reason behind your decision?” This makes sense because your why is often the trigger for taking action in the first place.

But psychologically, it’s useful to think of your why as something in front of you. Initially, it may have been the trigger for your action, but after that it becomes the purpose that pulls you forward. In other words, it’s the thing that gives you motivation.

For example, if your why for starting your own business is to have more control over your time, imagining yourself being able to take a day off whenever you want might boost your motivation to work on the new business.

In other words, your why is actually the primary source of motivation for your goal. But here’s the thing most people don’t realize…

It’s not enough to have a why; if you want your why to be truly motivating, it has to be sharp—specific, tangible, detailed, visceral, juicy!

To illustrate, imagine two people who want to start their own business, Teddy and Shauna.

They both want to start similar businesses and they both have the same why—to have more control over their time. But the details are very different…

- When you ask Teddy why he wants to start his own business he says I just want more control over my time. He hasn’t really thought much past that.

- When you ask Shauna why she wants to start her own business, she describes, as an example, how she doesn’t want to have to worry about how many personal days she has left if she wants to spend the day with her daughter on her birthday. She can just decide to take the day off and figure out how to make it work. She also explains how she’s a night owl by nature and does her most creative work late in the evening. She describes how excited she is to be able to align her work with her own energy instead of forcing herself to work at non-optimal times.

Now, all other things being equal, who’s why is going to be more motivating?

Yeah, obviously Shauna’s. Because her why is sharp—detailed, clarified, specific—it’s more compelling and motivating. But because Teddy’s is soft—vague, general, conceptual—it’s not going to provide nearly as much motivating energy.

So, whatever your goal is it’s obviously important to understand your why—your reason for doing it. But just as important, it’s critical that you sharpen your why—make it real and specific and visceral for yourself and you’ll find it far more motivating.

3. Create a PSP (Painfully Specific Plan)

Plans are paradoxical creatures…

- Superficially, plans feel confining—like they limit or constrain us. So we often resist them.

- And yet, many of us feel paralyzed in inaction, unable to pursue our goals or make progress on them precisely because we don’t have a clear enough plan. The ambiguity of what to do next or how achieving a goal will actually look is nerve-wracking, anxiety-producing, and ultimately, blocks us from making meaningful progress toward that goal.

For example, let’s say you wish you felt more motivated to look into a career change because you’re really unhappy with your work. You know this is something you want, you understand that it’s doable and your life would be measurably better if you were in a career that was more conducive to your talents and strengths, but you just never seem to do anything about it.

What’s going on here?

Well, one way of looking at it is that your plan for a career change isn’t very detailed. In fact, you arguably don’t even have a plan, really, you just have a goal.

A plan involves not only the goal or outcome but a series of steps or actions, each of which incrementally moves you toward the end goal.

Now, you might say, No, I know what I need to do. I just need to get online and start searching.

Well, that sounds like a nice first step, but actually it’s still really vague…

- Where exactly in the vastness of the online world are you going to go?

- What are you searching exactly? Google? A job board? A resume site?

- How much searching are you going to do or for how long?

- Is internet research the only way you’re going to research a new career?

This is where the concept of the Painfully Specific Plan comes in.

A painfully specific plan is a plan that’s so detailed and specific that it feels stupid.

For example, if the first part of your plan is to research careers online, you want to break that first part down into many smaller parts:

- For the next four weeks, at 6:30 pm on Tuesday evenings, I’m going to spend 30 minutes on my computer exploring potential new careers.

- By the end of each 30-minute session, I will identify 5 possible careers, and list at least two examples of jobs within that career for each. I will keep this list in a new Google Forms file called “New Career Research.”

- At the end of four weeks, on the following Tuesday at 6:30 pm, I will review all my lists and notes. I will choose 3 of the most exciting and interesting potential jobs.

- For the next three Tuesday evenings from 6:30 to 7:00 pm, I will explore each of those three jobs in detail. If possible, I will contact someone I know who works in that job or friend and ask if we can talk for 30 minutes. At a minimum, I want to ask them 5 questions:

- What’s the best part about your job?

- What’s something about your job you wish you had known earlier?

- How is your job different in day-to-day life than what you imagined it being?

- What qualities or skills make someone good at your job?

- Can you think of someone else who would be helpful for me to talk to about this job?

Now, the specifics of this plan aren’t important. What’s key is the level of detail and specificity.

Notice how the above example isn’t even the whole plan—it’s just a plan for part 1 of the bigger plan.

Also, look at how many artificial constraints and rules there are: specific times and palace, specific numbers of items, specific questions to ask, etc. Good motivating plans will often have a lot of somewhat arbitrary constraints. But even though they’re arbitrary and self-imposed, they serve the critical function of helping you be more specific and action-oriented in moving toward your goal.

Think about it, which of these plans are you more likely to end up following:

- Research new career.

- Spend 20 minutes on Saturday afternoon (on my way home from the gym) at the library browsing at least three career transition books. At the end of the 20 minutes, decide on one to rent and take home for future research.

Now, obviously getting a book about career transitions is just the first step of the first action of the first part of phase 1 of your career transition process. But at least it’s a start!

Here’s the takeaway:

- The more specific a plan is the more likely you are to take action.

- The more action you take toward your goal, the more motivated you will feel.

- The more motivated you feel, the more action you will take.

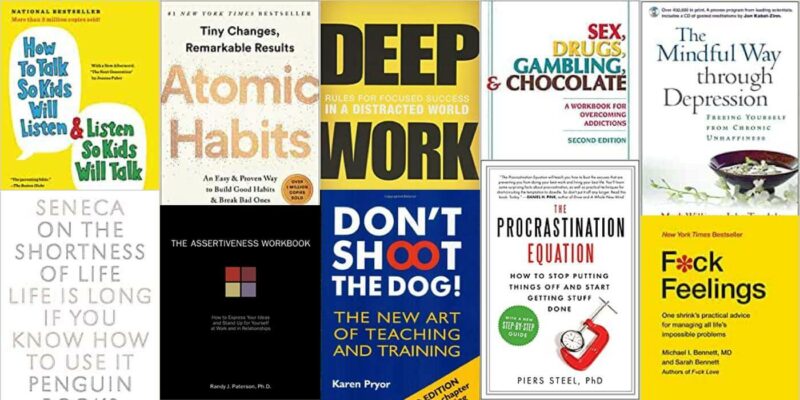

Learn More About Motivation

If you want to go deeper, I teach a course called Finding Focus that’s all about how to discover, clarify, and leverage your personal values to overcome procrastination and build lasting motivation in your professional, personal, or creative life.

15 Comments

Add Yours❤️

????

You are like a breath of fresh air amidst much cognitive smog, thank you!

Wow, thank you!

I agree 100%. Articles are clear, concise and immensely helpful – every single time!

Thanks, Joann 🙂

Great article!

Thank you!

You’re very welcome, Goffredo!

Very useful & interesting article. Thanks

You’re very welcome!

Great Article. I love the third step of creating a detailed plan, or PSP.

The article is simply true, and it’s very correct about motivation and one can build it professionally.

Sincerely, I wish that a greater number of individuals would avail themselves of the outstanding and critical forum that you provide.

The above methods improve very well

The story is completely true, and it’s very true that everyone can become more motivated.