To get the full value of joy you must have someone to divide it with.

― Mark Twain

Recently, several people asked me almost identical versions of the same question:

How can I cultivate more joy in my life?

One person went on to elaborate that…

Most advice out there is about limiting the downsides in life, but doesn’t say much about increasing the upsides.

This seems right to me. There’s a lot of good writing and advice out there about becoming happier through inversion. The basic idea is that the best way to become happier is to reverse the process and ask, How can I prevent myself from becoming unhappy?

I suggested something similar in a recent essay, Happiness Is a Subtraction Problem:

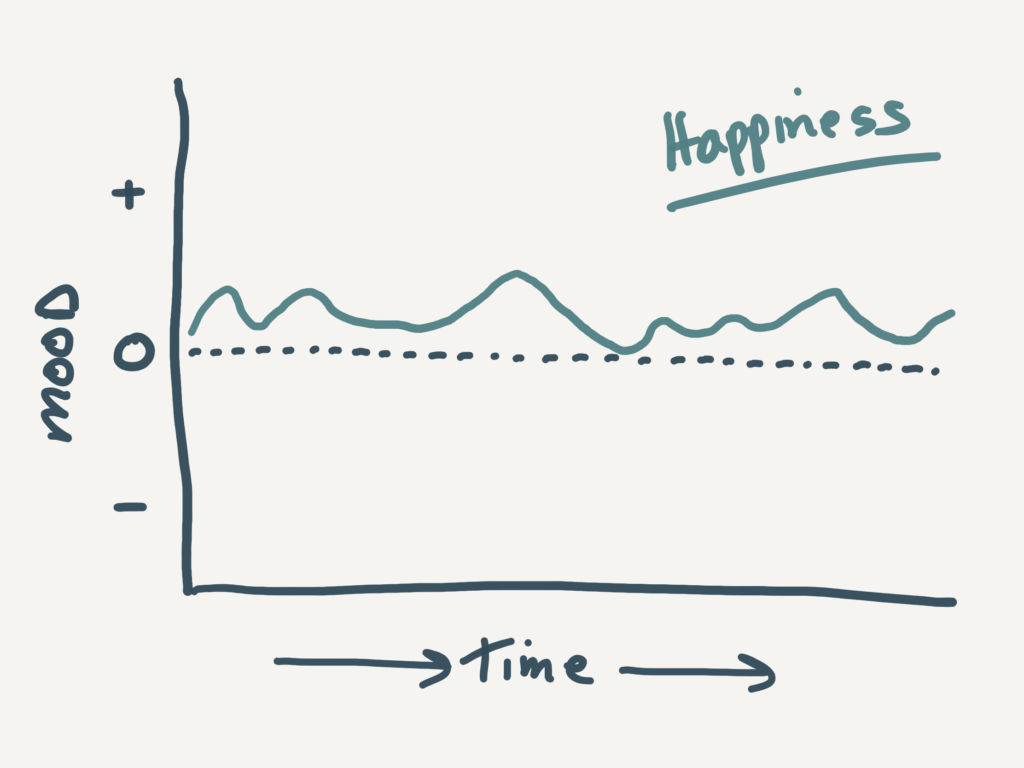

What if the ‘secret’ happy people know is that happiness has more to do with minimizing downside than maximizing upsides?

Maybe it’s boring, but for me happiness is what’s leftover when I subtract the negative experiences in my life from the positives, as I’d rather be consistently +5 than erratically alternating between -40s and +55s.

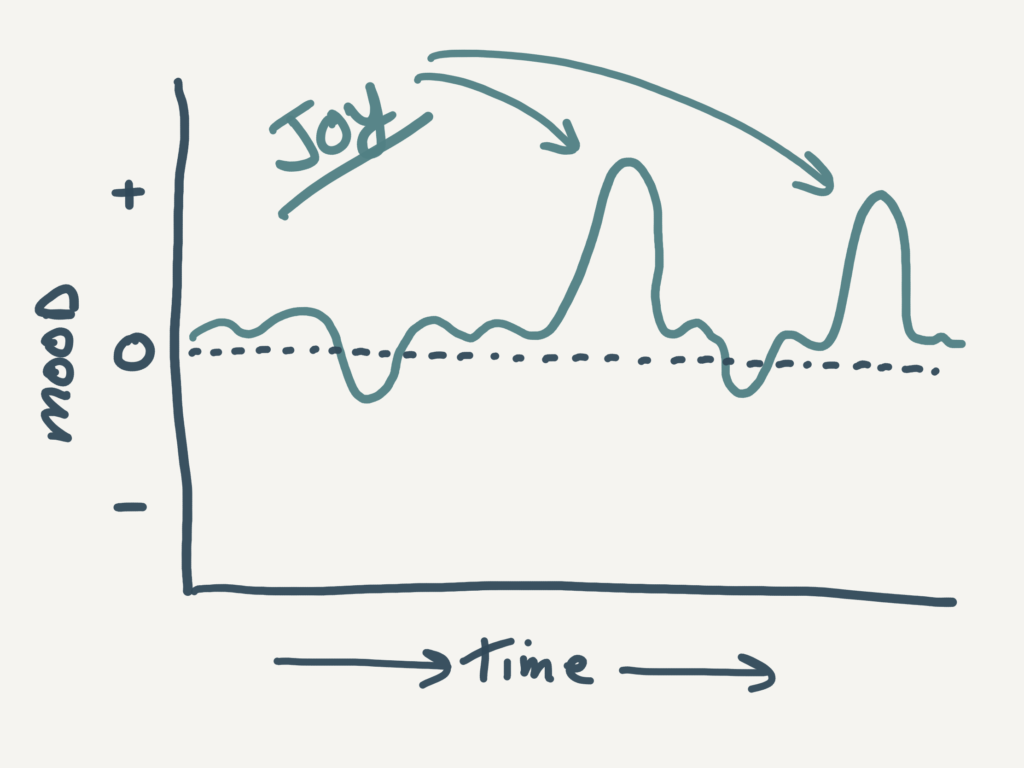

Whether or not you agree with that definition of happiness, it’s independent of the question posed by my readers: How can we increase the frequency of joy in our lives? In other words, regardless of what our baseline mood state is, how do you optimize for more peaks?

Historically, the field of psychology has been much more interested in the alleviation of suffering than the cultivation of joy. Which means I’m not sure a psychologist is necessarily the right person to try and answer this question…

I’m gonna give it a shot anyway.

But before we dive into the question of how to cultivate joy, we ought to spend a quick minute defining what it is exactly.

What is joy?

Here’s my working definition of joy:

Joy is an experience of intensely positive feeling, usually characterized by a mixture of excitement and connection.

Let’s unpack that a bit…

- An experience of intensely positive feeling… First of all, unlike happiness which I think of as a more or less steady state, joy is more of an acute and relatively short-lived experience. We experience moments of joy, usually on a scale of minutes or hours. Second, it’s intensely positive. While some might argue that happiness is more characteristic of the absence of suffering, joy is pretty clearly the addition of positivity above our normal baseline mood.

- Usually characterized by a mixture of excitement and connection… This is more speculative but to me the two characteristics that mark moments of joy in my life almost always involve at least these two elements: excitement and connection. Other variants of excitement might include passion, curiosity, stimulation, awe, etc. And while connection is often something akin to friendship or love between people, I think it can also be a sense of belonging with the world, nature, God, the Universe, etc.

Obviously joy is a big concept, and I’m sure my particular definition here does someone’s experience of joy a disservice. But it’s the definition creator’s dilemma to construct one that is sufficiently broad to be accurate yet narrow enough to be useful.

If you have thoughts, alternatives, criticisms, etc. I’d love to hear them in the comments section at the end.

Pressing on, let’s take this working definition of joy and get on to the main event: How can we cultivate more joy in our lives?

How to cultivate joy: a framework

Sadly, I don’t have any specific insights or advice about types of experiences that will lead anyone to joy. For one person, the answer might be spending more time in nature. For another, it might involve a change in their social context. And for others, it might involve a lot of psychedelic substances.

But I do have some thoughts on how to think about this question of cultivating joy so that you might get a little closer to discovering those answers for yourself.

I’ll call it a framework for cultivating joy.

To begin, let’s start by thinking about the opposite of joy—suffering.

Most forms of emotional suffering are the result of an interaction between internal factors and environmental factors. This is called the diathesis-stress model of psychopathology. Depression, for example, is often the result of an interaction between environmental stressors like divorce, job loss, abusive relationships, etc. and cognitive vulnerabilities like the tendency to ruminate on past failures, negative self-talk, etc.

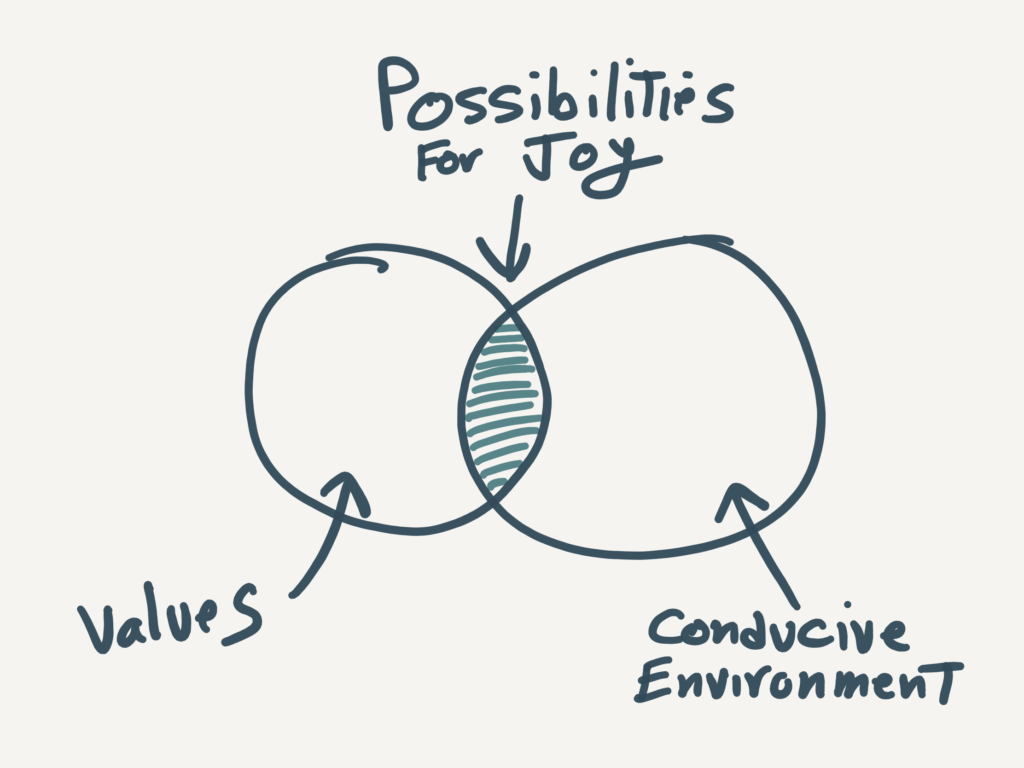

Maybe we could invert this model and use it as a framework for cultivating the opposite of suffering—joy.

In other words, what if joy is a function of getting the right combination of internal factors and external circumstances? When I say internal factors, I’m thinking of things like preferences, values, interests, etc. And when I say external factors, I’m thinking of environmental conditions like being around certain people, spending time in certain environments (libraries, forests, concerts, etc.), and so forth.

This leads to a set of questions that might be useful if you want to maximize your odds of experiencing joy:

- What are my most authentic preferences and values? What do I truly enjoy and find meaningful?

- What circumstances are most conducive to those values? What situations bring out the best in me?

- What changes can I make in my life so that I spend more time in circumstances conducive to my true values?

To make all this a little more concrete, let’s walk through each of these questions and look at some examples.

1. What are my most authentic preferences and values?

Superficially, it doesn’t seem like an especially hard question:

What do I really want?

But to answer it well is surprisingly difficult because we often get confused about what we want. Specifically, we can easily fall into the trap of wanting what other people want or what we think we should want.

Choosing a career is notoriously susceptible to this dilemma. Did you decide to become an attorney because you actually wanted that and value it in a deep way? Or did your choice have more to do with the fact that all the men in your family have been attorneys for the past three generations and you didn’t want to be the one to break with tradition?

Or consider choosing a spouse or even the decision to marry in the first place. There are enormous cultural pressures to get married and to marry the right type of person. And it can be difficult to tease out whether your preferences in a partner are the result of what you actually want vs what you think you should want.

Of course, clarifying your true preferences and values can be far more mundane than choosing a career or spouse. Consider hobbies, for example:

- Do you truly enjoy going out to bars on Friday nights? Or do you do it because that’s what you’ve always done and you’re not really sure what else a 25-year-old is supposed to do for fun at the end of the week?

- Do you actually enjoy camping? Or do you do it because your spouse enjoys it?

The point is—big or small—our values and preferences are easily influenced by those of other people and even society at large. And while there are likely many ways to go about discovering your own authentic values and preferences, I think a good first step is to simply be clear on how many of your values or preferences are not in fact your own.

One final point: There’s nothing wrong with sharing similar values or preferences. And there’s nothing wrong with taking on or inheriting preferences from other people. In fact, I think this is a natural process and one of the primary ways we discover our own values and preferences. My point is simply to take some time to verify that values you share or inherit are in fact ones you genuinely enjoy and find personally meaningful.

And if after some reflection you discover that many of your values or preferences are not actually things you enjoy or believe in, it might be time for a shake-up.

2. What circumstances are most conducive to my authentic values and preferences?

I really enjoy the board game Monopoly. And I have since I was a kid.

The only problem was (and is) it’s difficult to find other people to play with. And even more challenging is finding people to play with who are capable of doing so without getting super intense, hyper-competitive, or emotionally distraught when you purchase the one property they really wanted.

The point is, no matter how much I genuinely enjoy Monopoly, it doesn’t matter if I don’t have the right people to play with. More generically, most values and preferences are at least partly context-dependent—they only take effect in the right circumstances.

To mix my metaphors, values and preferences typically operate under a lock and key dynamic: On its own, a key usually isn’t all that interesting, useful, or fun. But when paired with the right lock, it can literally and figuratively open up doors to amazing things.

Which means, once you’ve identified some genuine preferences and values with a good amount of joy-potential, it’s important to realize that that potential probably won’t get unlocked without the right set of circumstances.

Here’s an example:

Suppose you’re passionate about street photography. But after moving from downtown Chicago to a rural small town in Iowa, it’s a lot harder to just walk out your door and start doing street photography and getting the joy that goes along with it.

One of the things that brings me a lot of joy (other than Monopoly) is meaningful conversations about interesting ideas. In high school, my coaches in sports used to get irritated with me when, after a “devastating” loss, I didn’t seem to care at all and was perfectly happy losing myself in a good book on the bus ride home, having an exciting conversation (of sorts) with the author of my book.

One of the reasons I ended up choosing therapy as a profession is because it allowed me to have meaningful conversations about interesting ideas all day long! On the other hand, no matter how exciting it might seem to be a professional basketball star, for example, I probably wouldn’t be very happy doing it because I just don’t like basketball nearly as much as a good conversation. And I probably wouldn’t have experienced nearly as much joy since the environment of a pro basketball player is potentially less conducive to meaningful conversation than psychotherapy.

To sum up, the joy-potential of most of our authentic preferences and values will only be unlocked with the right circumstances. Which means we ought to be thoughtful about the people, situations, and environments in our lives and how they impact us.

3. What changes can I make in my life so that I spend more time in circumstances conducive to my true values?

This is perhaps the most challenging of the three to implement.

Suppose after some serious reflection and contemplation, you’ve realized that you’d have a lot more joy in your life if you were able to spend more time playing classical guitar (a true passion) and spending more time in music venues and around musical people. The “only” problem is that most of your life as it stands now depends on you sticking to your well-paying corporate job that leaves little time for classical guitar.

Especially once we hit a certain age, making significant changes to our lives is difficult. It’s one thing to quit your steady corporate job to pursue your passion as a musician when you’re 23, single, and relatively content to sleep on couches and eat ramen noodles. It’s a very different thing to do it when you’re 43 with a mortgage and 3 kids.

The trap here, I think, is all-or-nothing thinking—the implicit belief that to inject your life with a more significant amount of joy, you need to completely alter it. And the solution is incrementalism.

The incrementalist attitude suggests that you can start small and work up toward increasingly big changes.

So, if you want to pursue more time with classical guitar, what if you started by simply playing a little more on the weekends? Even the busiest of us can probably manage an extra 20 minutes a couple times per week.

Maybe from there, you consider playing at an open mic night once a month at a neighborhood bar, which would give you more opportunities to meet like-minded people.

Then after a year, say, of playing guitar consistently—including on your own and during open mic nights each mont—you might have discovered:

- A) Just that amount of change was actually sufficient to significantly increase the amount of joy in your life. Or…

- B) You’re more confident that you do really want to make a serious change to your life—it’s not just an idealistic dream or whim—and start taking concrete steps toward something bigger like a career change or job shift.

To sum up: Even if big changes seem too scary or ill-advised, there are almost always smaller, more modest changes you could experiment with. Just don’t fall into the trap of all-or-nothing thinking.

The joy of experimenting

Like I said, I have no rules to follow or practical tips for finding more joy in your life.

Instead, I’ve laid out a few general principles in the form of questions that might be helpful getting started at least thinking about how to think about the problem:

- What are my most authentic preferences and values? What do I truly enjoy and find meaningful?

- What circumstances are most conducive to those values? What situations bring out the best in me?

- What changes can I make in my life such that I spend more time in circumstances conducive to my true values?

Ironically, having spent an entire essay describing a method for how to think about cultivating joy, maybe the most important idea here at the end isn’t really an idea at all: just try something.

Good scientists understand that no matter how brilliant the theory, it doesn’t mean anything without experimentation—without taking practical steps to observe, measure, test, and reformulate.

I suspect the same is true in the search for joy.

While some initial theorizing will likely be helpful, in the end maybe the best we can do is experiment our way into joy.

13 Comments

Add YoursWhen I was a child, my uncle would send me tickets for the circus every year for my birthday. I despised the circus (it was THE circus in NYC)–too much stimulation with the three rings and crowds and even as a kid, knowing what went into the training of the animals and how they suffered/were abused, but I couldn’t speak up about it both as not to hurt his feelings and to not appear like a freak because what kid doesn’t like the circus? And this carried on through adult life, not wanting to admit that what most people thrived on were horrible for me.

I appreciate your acknowledging that much as you love Monopoly, you don’t just want to play with anyone. I know a lot of people who will play cards and other games, as well as do sports/hiking and even travel with people they dislike, just to have another person(s) for the activity. I’ve always wondered how they could enjoy said activity if they didn’t like/respect/enjoy their companions. For years I tried to befriend and do activities/socialize with anyone who was available (even organizing Meetup groups, which was so outside my comfort zone as an introvert!). It got to be quite the ego trip, telling myself I was a good person doing the right thing by giving anyone and everyone a chance (usually unlimited chances) and befriending people with undesirable (at least to me) characteristics because I was putting lovingkindness into action. But this wasn’t the right thing for me and even if I was taking a little boredom away from some of these people and offering them companionship, I ultimately had to acknowledge that it was hurting me more than it was helping them. Nowadays I concentrate on self care and am very careful (some might stingy) as to who I spend time with—but this gives me peace of mind/happiness and allows me to have the time and energy to be with and help those people who truly want, appreciate, and could actually benefit from spending time with me.

Thanks for this Ellen. It’s so hard to avoid the trap of trying to be everything to everyone. Glad you’ve found some success with that!

An interesting article Nick, thank you so much.

Has the enforced lock down caused people to find more joy in the simple things of life, not having to be on the hamster wheel of life, just more aware of having to make do with what is.

I think that the perception that joy is something to attain an interesting one.

If we substitute the word love for joy then joyous vibrations are felt when we do loving things or others do loving things towards us.

I like the way Nick makes us all think about things,his words truly resonate

Best Wishes to all

Thank you, Rita! It’s a good question about the relationship between love and joy. Will have to ponder more!

Really nice, Nick! I’m on this path to find what brings me more joy and it is been amazing 🙂

Thankyou for this.. I needed it. I appreciate you taking the time..

Always en(joy) reading your essays. Great points. I especially like the idea of just experimenting. Thanks for sharing your time and energy with us.

A lovely article Nick but I think that the subtraction theory of happiness really points to a state of contentment rather than happiness. Of course it’s entirely possible that there is no such thing as happiness. Maybe there is just a continuum between two states: joy and contentment.

Nick,thank you for my word of the day. Incrementalism. A big word for simple actions.

The best part…anyone can do it. For anything. Satisfaction guaranteed;)

Hi Nick! I’m very new in this, but your articles are truly amazing and taking me to right path. so appreciate it!!!

I love how simple this is. But it seems like the necessary Step 0 is to know what brings you joy. Any tips for realizing what brings you joy after being beaten into an automaton by a corporate consumerist society?

very well articulated. It is actually the question “what do i really want?” that most people are unaware of and which eventually leads to the sad state of affairs.

well thought of three questions, which will actually define joy for everyone, when one will ponder seriously.

I really like reading your Articles – monday motivation.

Nick, I like your thinking. I am not a fan of the word happy it is too broad a fuzzy word. I like the word flourish as a term for what is a happy life. The thinking comes from Martin Seleman’s whose work I suspect you know. His book is great Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being

The 5 part model is

Joy: Your def

Connection/Relationships that have meaning

Purpose beyond yourself

States of Flow

Meaningful accomplishments of goals

I would add reasonable health and basic needs met.

The one part I dance with is working hard in ways that may not be so much fun for goals that feel better upon completion but the work part can be high and completion short-lived like writing a long article or book.

What do they say I don’t like writing but like having written. Do you ever experience that?