“There are two kinds of technical problems: there are the known unknowns, and the unknown unknowns.”

— Lt. Gen. William B. Bunker

“The most terrifying thing is to accept oneself completely.”

— Carl Jung

You’re probably familiar with the concept of blind spots:

- That section of the road behind you that you can’t see with either your side or rearview mirror that makes you extra cautious changing lanes.

- Or when your shopping cart at Costco is so overstuffed you can’t see over it and have to peer around the side to find your way to the checkout line.

What’s less familiar—but no less significant—is the concept of psychological blind spots, which are aspects of your psyche—a belief, a fear, a desire, a talent—that are blocked from ordinary awareness.

A few examples:

- Early in my training as a therapist I worked with a gentleman who—in the middle of one of our sessions—screamed at the top of his lungs that he didn’t have an anger problem before stomping out of the room and slamming the door. You might say that acknowledging anger was a blind spot for him.

- Another one I see often in my consulting work with teams is a blind spot around conflict. A lot of organizational cultures over-value conscientiousness and end up using it unconsciously as a defense mechanism against fear of conflict which creates stress, drama, and inefficiencies in how they work together. Overvaluing conscientiousness creates a cultural blind spot around conflict.

- Recently, I’ve been doing some reflection on my own blind spots. Specifically, I’ve been thinking a lot about how a trait I usually see as a superpower, discipline, creates some serious blind spots for me. For example, because I value discipline so much I often project that value onto others which leads to unrealistic expectations and all the frustration and impatience that go along with them. So for me, my strength around discipline was creating a blind spot that was hiding problems around expectation management.

I bring up this issue with psychological blind spots because I’m finding—both personally and professionally—that becoming more aware of our blind spots is a prerequisite for most inner work.

The things that keep us stuck in life often live inside our blind spots.

Of course, given that a blind spot is by definition hidden from view, uncovering them can be challenging. People often seek out coaches, consultants, and therapists precisely because it’s much easier to see someone else’s blind spots than our own. But it’s not impossible to identify your own blind spots and begin shining some light on them. And one of the best ways I’ve found to do it is with a little exercise I call shadow mapping.

I’ll explain what shadow mapping is and how to get started with it in a minute. But first, we need to take a slight detour to explore the broader concept of shadow work.

Demystifying Shadow Work

Carl Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist and influential theorist of psychology. In fact, next to Freud and maybe William James, he’s arguably one of the most influential figures in all of psychology. One of his central ideas was the concept of the shadow.

For Jung, the shadow is the part of our psyche where we repress or hide away unwanted aspects of ourselves: it could be emotions like anger or sadness; it could be desires like an embarrassing affection for Taylor Swift music even though you’re a 40-year-old man; crucially, it doesn’t have to be negative or shameful things—often the things we’re most likely to stuff away in our shadow are talents or aspirations that have so much potential energy they terrify us.

One of my favorite illustrations of the shadow and how it works comes from the poet and author Robert Bly in his short essay The Long Bad We Drag Behind Us:

When we were one or two years old we had what we might visualize as a 360-degree personality. Energy radiated out from all parts of our body and all parts of our psyche. A child running is a living globe of energy. We had a ball of energy, all right; but one day we noticed that our parents didn’t like certain parts of that ball. They said things like “Can’t you be still?” Or “It isn’t nice to try and kill your brother.” Behind us we have an invisible bag, and the part of us our parents don’t like, we, to keep our parents’ love, put in the bag. By the time we go to school our bag is quite large. Then our teachers have their say: “Good children don’t get angry over such little things.” So we take our anger and put it in the bag. By the time my brother and I were twelve in Madison, Minnesota, we were known as “the nice Bly boys.” Our bags were already a mile long.

The shadow can be dangerous if we leave things there too long without revisiting them, and as a result, they end up “coming out” in unhealthy ways. Your tendency to clean the house compulsively, for example, might be a manifestation of your desire of assertiveness and agency being left too long in the shadow. Or your self-sabotaging marijuana habit might be a manifestation of stuffing your ambition too far into the shadow because you’re afraid of committing to big goals and failing.

Viewed through the lens of the shadow, many of our chronic emotional struggles can be reframed as unhealthy expressions of authentic needs we’ve ignored.

The implication is that if we want to get unstuck, break a bad habit, or follow through on our goals and aspirations, there’s a good chance shadow work and bringing more awareness to the hidden parts of ourselves (i.e. blind spots) could help.

But one more thing I want to clarify before we move on: putting things in the shadow isn’t necessarily bad. Children need to learn how to contain their aggression if they’re going to assimilate into society. And the impulse to pick your nose at the dinner table is best inhibited. What’s more, there are plenty of things that, depending on the time or your stage of life, are useful outside the shadow and at other times need to be in the shadow. For example: if you’re a first year medical student, your desire to do things “your way” during a surgery is probably best left in the shadow; but if you’ve been a practicing surgeon for 15 years the bigger danger might be to fall into the habit of always going “by the book” and never letting your autonomy and creativity out of the shadow.

So remember, the shadow is not an inherently good or bad thing, nor are the contents within it or outside of it. As usual when it comes to managing difficult parts of ourselves, it’s not about fixing or getting rid of them so much as changing our relationship to them—which is to say, with ourselves.

Okay, let’s get to shadow mapping…

What Is Shadow Mapping?

Shadow mapping is a shadow work exercise I’ve developed to help you overcome inner obstacles or problematic behavior by exploring your personal blind spots. Specifically, shadow mapping relies on the concept of inversion to help us access our blind spots indirectly and increase our self-understanding.

Here’s the key idea:

Often our deepest fears and most profound gifts hide in the shadows cast by our strengths and convictions.

Or as Jung put it much more poetically:

The brighter the light, the darker the shadow it casts.

For example:

- Your strength as an analytical thinker might be casting a shadow that hides your tendency to avoid taking intellectual or creative risks.

- Your strength as a “people person” might be casting a shadow hiding a weakness or vulnerability around fear of conflict and poor assertiveness.

- Your strength as a highly conscientious person might be casting a shadow that hides a deep desire to be more autonomous and independent.

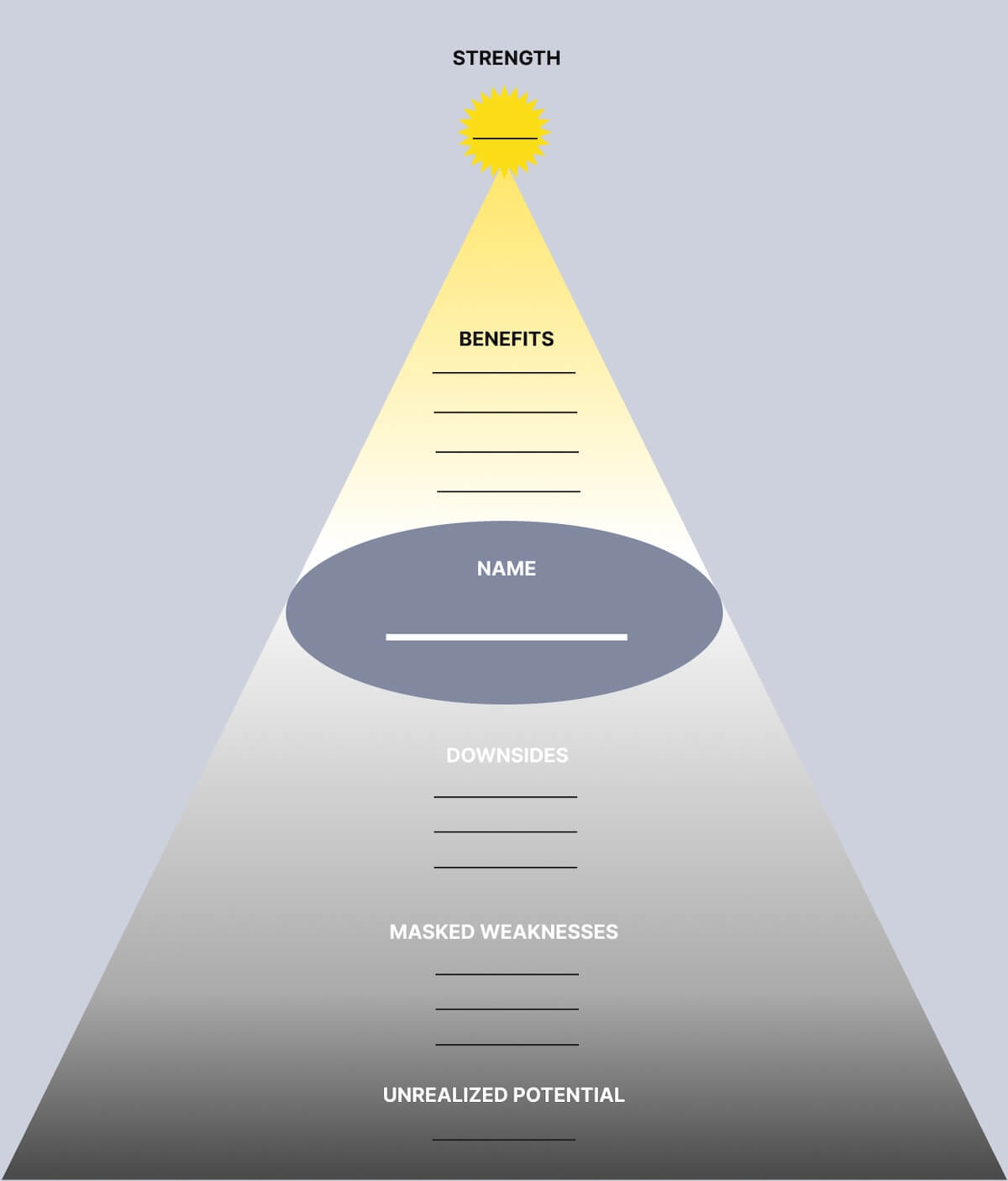

In other words, shadow mapping gives you a structured method for reflecting on how your strengths might be hiding fears, weaknesses, and even, unrealized strengths and potential.

How to Do Shadow Mapping

Here’s a brief overview of the steps involved in shadow mapping.

Shadow mapping, a five-step process:

- STEP 1: Identify Strengths. Brainstorm a handful of characteristics or attributes that you consider personal strengths. For example, three of my strengths are disciplined, friendly, and curious.

- STEP 2: Brainstorm Benefits. Pick one of those strengths you identified to focus on and list a handful of examples of how you or others benefit from that strength. For example, if I chose disciplined as my focus strength, I might list reliable, easy-to-work-with, and productive as the benefits.

- STEP 3: Identify Side Effects. Now consider what some negative side effects of that strength might be. For example, a negative side-effect of being a pretty disciplined person is that I get easily frustrated when I have to work with people who aren’t very disciplined. And unchecked, that frustration can lead to resentment, impatience, and judgmentalness.

- STEP 4: Identify Weaknesses. Next, ask yourself: What are some personal weaknesses or vulnerabilities that my strength masks or helps me avoid thinking about? For example, I have a limiting belief that “I’m not creative.” It’s uncomfortable—embarrassing, sad, and anxiety producing—to acknowledge that I don’t believe I’m creative (even though intellectually I don’t think it’s really true). I often “use” discipline and a strong work ethic to distract from that limiting belief around creativity. I know it’s a thing, but because I’m either afraid or unwilling to really examine and confront it, discipline “helps” me avoid it or procrastinate on working on it.

- STEP 5: Identify Unrealized Potential. Finally, the deepest level of the shadow involves what I think of as unrealized potential or a feared higher calling. This is a talent, trait, or aspiration in you that is so big—and has the potential to be so good—that it terrifies you. For example, ambition is one of mine. Deep down, I believe that I have the capability to do something great—epic even—with my life. And that belief scares the hell out of me, which is why for a long time it was stuffed down in the darkest corner of the shadow. To use a baseball metaphor: Being exceptional at getting on base is a good way to avoid swinging for the fences. Or a writing metaphor: Being really disciplined about writing weekly essays is a great way to avoid writing a book.

That’s the basic architecture of the exercise, but I’ve found it to be easier and more fun to do it visually like this:

Shadow Mapping Tips and Suggestions

If you’re having trouble brainstorming strengths, ask someone who knows you well. Just like other people often have an easier time seeing our blindspots, they sometimes have more clarity on our strengths too. Here’s a little script you can use:

I’m doing this self-awareness exercise called shadow mapping. One of the first steps is to list your personal strengths, but I’m a little stuck. What are some qualities or attributes in me that you think are strengths?

Don’t expect to be able to do the whole exercise in one shot. It might take a few passes before it starts to feel more or less complete. Also, if you get stuck doing it with one strength, feel free to try another, then come back to the initial one later.

The three levels of the shadow are not completely discreet. If you’re having trouble deciding if something goes in side effects or weaknesses, for example, don’t worry too much about being exactly correct—the fact that you’re thinking about it and grappling with it is the real benefit of the exercise. And remember: Things in the shadow are hidden, but not intrinsically good or bad.

A common question I get with shadow mapping is: What do I do with my shadow maps? The main benefit of shadow mapping is to bring hidden or obscured parts of yourself into conscious awareness, not necessarily to do anything with it. Because the more those things are part of your conscious life, the more likely you are to begin to act on them—mitigating side effects, remediating weaknesses, moving toward unrealized potentials, etc. That said, one of things I’ve found especially helpful as a next step after doing some shadow mapping is to start talking about what you’ve discovered with other people—a spouse, good friend, partner, etc. Often they can help you elaborate on and fill out details you uncover in the initial exercise.

As a variant of the exercises, try starting shadow mapping with a deeply held value or beliefs rather than a strength. Often values and beliefs can cast shadows just like a strength or talent can.

Benefits of Shadow Mapping

I hope that by this point I’ve already convinced you that being more aware of our blind spots is a pretty good thing. But to make it a little more concrete, here are a few of the areas where I’ve found shadow mapping to be most helpful.

Deepening Self-Awareness. Even if you don’t have a specific problem to overcome or goal to achieve, shadow mapping can help you become more self-aware and understand yourself better. Specifically, it’s most helpful for understanding non-obvious parts of yourself or for re-evaluating and deepening your understanding of a part of yourself that you assumed you understood but perhaps not as fully as you realized.

Correcting Bad Habits or Self-Sabotage. You don’t have to buy into Jung’s theories whole hog to see the intuitive insight that the things we keep hidden—consciously or not—often exert negative effects in our lives. Fear of anger leading to chronic passivity and people-pleasing, for instance. Or unrealized professional potential leading to chronically sub-optimal career choices. If you have some kind of bad habit, unhealthy pattern, or self-defeating behavior, it’s possible that at least part of what’s maintaining it lives inside one of your psychological blind spots. And shining a light on those blind spots with some form of shadow work like shadow mapping could very well be the necessary first step to letting them go.

Resolving Interpersonal Conflict. It’s a truism that you can’t have healthy relationships with other people if you don’t have a healthy relationship with yourself. The emotionally stunted husband who’s overbearing and cold because he’s afraid to be vulnerable is a classic archetype. Or the passive-aggressive manager who uses their authority over others to feel powerful and in control. But acting on that insight can be surprisingly tough. How exactly do we create a healthier relationship with ourselves? Shadow work—and shadow mapping, specifically—helps you gain insight into parts of yourself that you’re not especially aware of—perhaps because they’re scary or shameful. But once you understand these parts of yourself better, it’s easier to start building a relationship with them: validating them instead of criticizing them, for example. Or talking about them instead of overcompensating for them. If you have chronic interpersonal issue with another person, there’s a good chance a big part of the reason why is that you have conflict inside yourself—and that conflict is probably in the shadows.

Phase of Life Transitions. Putting things into the shadow and taking them out ought to be a dynamic process. When you’re in the early-stages of your career, it might make sense to put some amount of ambition and creativity in the shadow and emphasize conscientiousness and discipline instead while you “learn the ropes” and “cut your teeth.” But as you mature professionally, that ambition and creativity should probably be brought out of the shadow—even if it means putting some of your discipline, for instance, back in. Very often when people struggle with phase of life transitions—getting married, having kids, changing careers, divorce, going back to work, etc.—it’s because there are parts of themselves in the shadow that need to be better understood and expressed.

Shadow Mapping Examples

Here are a few shadow mapping examples from former clients I’ve worked with. Note that I’ve changed their names and some of the details to preserve confidentiality.

Jennifer the Accountant

STEP 1: Identify Strengths. Hard-working, sensitive, observant.

STEP 2: Brainstorm Benefits. Focus Strength: Sensitive. Benefits: Empathetic and a good listener; intuitive; I’m a good friend; my clients really respect and trust me.

STEP 3: Identify Side Effects. I get emotionally overwhelmed. I tend to “take on” other people’s stress.

STEP 4: Identify Weaknesses. Being assertive about what I want. Setting boundaries is really uncomfortable—to the point that I usually don’t. I’m so used to absorbing and feeling what other people want that I’m weirdly insensitive to what I want. I usually adopt a supporter or helper role professionally rather than doing my own thing.

STEP 5: Identify Unrealized Potential. Starting my own business. My mother built her own very successful business from the ground up. I’m so proud of her. But I wonder if I’m afraid to do something similar because I wouldn’t be able to live up to her or it would feel like I was competing with her?

Allan The Burned Out Executive

STEP 1: Identify Strengths. diligent, persuasive, logical

STEP 2: Brainstorm Benefits. Focus Strength: logical. Benefits: make good decisions, reliable, admired, respected, stable.

STEP 3: Identify Side Effects. I take on too many things that are energy-draining rather than giving. Bored. Uncreative.

STEP 4: Identify Weaknesses. Taking the logical path is a very good excuse for never taking a risky path. I can be dismissive of people who don’t think as logically and analytically as I do—even judgmental sometimes. I’m so used to making the right decision—and having people trust that I will—that I almost never experiment or try things I’m not good at.

STEP 5: Identify Unrealized Potential. It’s cliche, but I’ve always wanted to write a book. Very few people know it but I’m kind of a fantasy nerd—I read fantasy books all the time. And ever since I was a little kid I’ve always wanted to write my own.

Jess the Prodigy

STEP 1: Identify Strengths. smart, charismatic, creative

STEP 2: Brainstorm Benefits. Focus Strength: smart. Benefits: people admire me. Fast learner. I can win just about any argument. I really believe I could do—and be really good at—just about anything.

STEP 3: Identify Side Effects. Laziness. Procrastination. Anxiety about decision-making.

STEP 4: Identify Weaknesses. I default to more schooling to avoid committing to a type of work or profession. I’m not afraid to be vulnerable, but it’s easy for me to stay very intellectual in my relationships because it’s what I’m most comfortable with. intimacy

STEP 5: Identify Unrealized Potential. I really want to have kids. I’ve wanted to since I was in middle school. But it’s weird because I’m pretty smart everyone expects me to be a rocket scientist or something. But I kinda just want to have a bunch of kids and raise chickens and shit like that. Sounds dumb when I write it out like this.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning more about shadow work, here are a few resources I’ve enjoyed:

- Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Jung’s autobiography that, among other things, recounts his own shadow work.

- Owning Your Own Shadow: Understanding the Dark Side of the Psyche. A short introduction to the shadow by analyst Robert Johnson.

- A Little Book on the Human Shadow. This is the book from which I took the excerpt The Long Bag We Drag Behind Us by Robert Bly.

Learn More

If you enjoyed this essay, here are a few more from me that might be helpful:

Work with Me

If you’re interested in working with me directly, I run a semi-annual emotional resilience masterclass called Mood Mastery. I also have a small private coaching practice for 1:1 work.