As a psychologist, I’m frequently asked a seemingly simple question:

What causes depression?

My answer is always the same:

I have no idea.

At this point, the face of the person asking the question quickly morphs from eagerness to perplexity. They usually follow up with something along the lines of:

What do you mean you don’t know what causes depression? You’re a psychologist, aren’t you?

Now that they’re sufficiently perplexed—and a bit riled up—I know I’ve got their full attention. Which is important, because the concept I introduce next is subtle:

It’s true, I have no idea what causes depression because I don’t think there is one cause of depression. But, I do know what maintains it.

In this article, I want to unpack that explanation, and along the way, accomplish two practical things:

- Explain why the question of what causes depression is complex, and why any simplistic answer should raise serious red flags in the mind of any thoughtful person.

- Show how two psychological habits—rumination and avoidance—maintain depression, regardless of the cause(s). Consequently, thinking about depression in terms of habits is the most pragmatic strategy for most people to begin addressing depression.

Whether you struggle with depression yourself, have a loved one who does, or are simply curious to better understand a very misunderstood phenomenon, I hope this article will be useful to you.

The “cause” of depression is far more complicated than we think

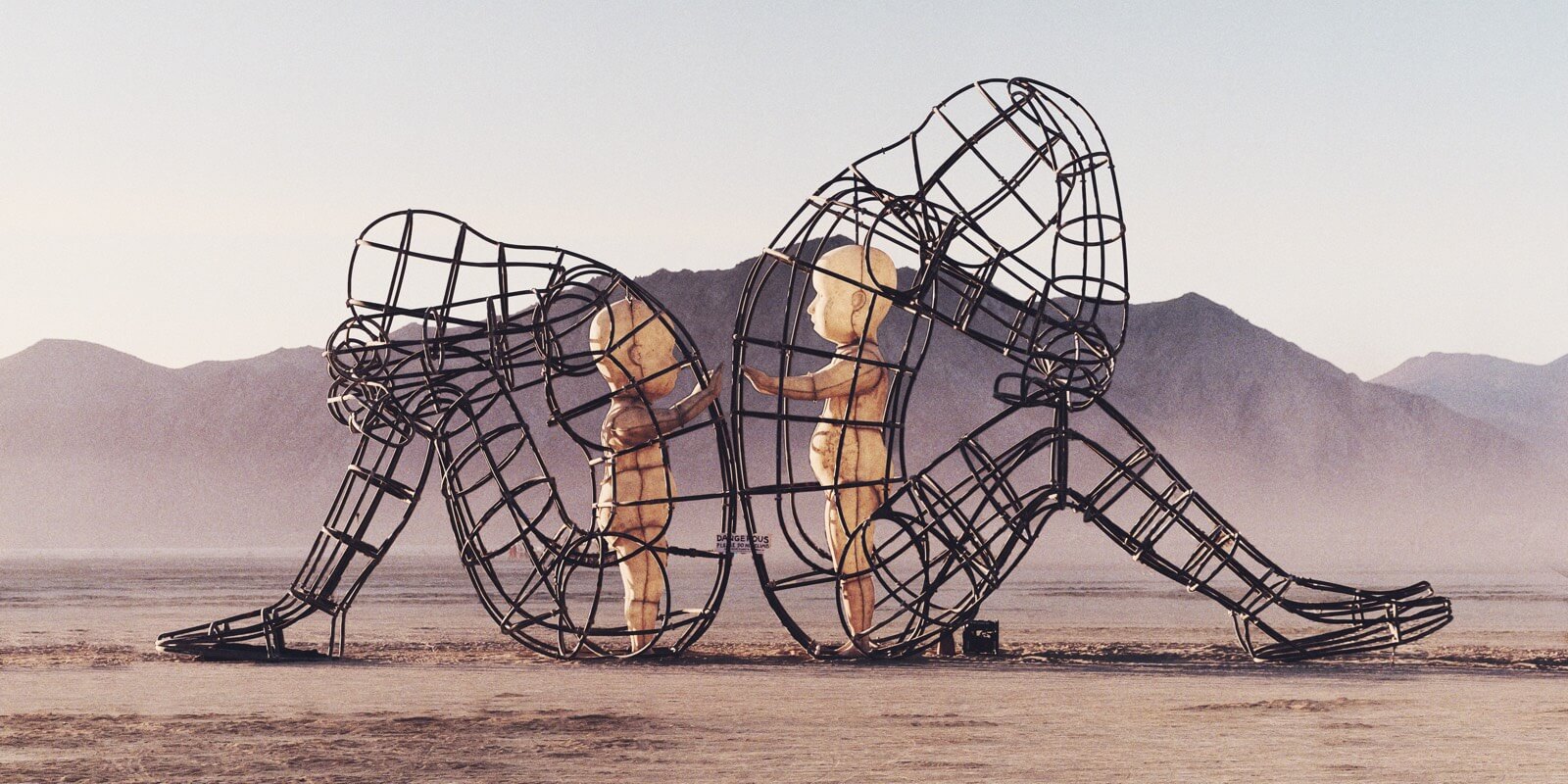

What if depression is, in fact, a form of grief—for our own lives not being as they should? What if it is a form of grief for the connections we have lost, yet still need? —Johann Hari in Lost Connections

As a society, we’ve been sold (figuratively and literally) the idea that depression is simply a “chemical imbalance” caused by a deficit in neurotransmitters like serotonin. Consequently, the simple (and profitable) solution is a drug that increases your serotonin and restores your brain’s chemical balance.

Nothing to it, right?

Sounds great. The only problem is, there’s little real evidence of any sort of chemical imbalance at play in depression; in fact, the chemical imbalance theory of depression has been dead for decades because there’s no actual research to bear it out.

This should dampen our surprise somewhat when we learn that medicine has been trying for the better part of a century to treat depression with drugs and the results have been tragically disappointing, often no better than placebo. And when research does suggest a positive effect over and above what you’d expect from placebo, the effect size is typically quite small, the duration of benefit short, the side effects significant, and there’s the very grave possibility of a massive file-drawer effect at play.

My point here is not primarily to criticize the pharmaceutical industry and psychiatric medicine; in fact, I’m quite glad we have drugs and psychiatrists, even if I think they’re not always correct in the way they conceptualize mental health.

Instead, I want to set the stage for a broader, more nuanced perspective on depression.

The misuses of neuroscience to explain depression

As a psychologist who spends hours each day trying to understand the lives of people suffering from a range of mental health struggles including depression, low serotonin or a “chemical imbalance” is a shockingly reductive way of thinking about a person’s mental health struggles.

Even if advances in neuroscience do lead to finer-grained analyses that show reliable neurochemical changes in the brains of depressed individuals, that simply begs the question: What caused those changes in the first place?

If you say genetics, proceed directly to jail, do not pass go, do not collect $200.

Any serious bio-medical scientist will tell you that for the past 20+ years we’ve known that—when it comes to human behavior—it’s foolhardy to try and think about genetics (i.e. how genes affect behavior) without also thinking about epigenetics (i.e. how behavior and environment affect genes).

Far from the one-way street we imagine them to be, genes are better thought of as 12-lane bi-directional superhighways, almost constantly affecting and being affected by the broader environment.

All that’s to say, the superficial glamour and psuedoneuroscientific appeal of the biochemical model of depression have blinded us to the vast and diverse realities of those who suffer from depression.

We talk excitedly about the latest research into how serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine affect mood, or the newest drug that promised to finally cure depression (ketamine is the latest “it” drug for depression).

But all the while we turn a blind eye to persistent loneliness and social isolation, abuse and trauma, poverty and chronic stress, excessive familial and cultural pressures, chronic illness and disease, substance abuse and addiction, lack of meaning and purpose, deep-seated regret and shame, as possible causes of depression.

If you give it a few minutes of thoughtful contemplation, it’s difficult not to realize that the causes of depression are as diverse and multifaceted as the histories and contexts of the people suffering from it.

No doubt brain chemistry and genetics play a role in peoples’ experience of depression, but we can’t let this distract us from the obvious social, psychological, cultural, and structural factors so evidently at play in the lives of those suffering from depression.

Which is why my answer to the question of what causes depression quite intentionally begins with, I have no idea.

So how should we think about depression?

The myriad potential causes of depression for an individual human being with their own unique history and context presents a matrix of possible causes so complex that a simple answer to the question of what causes depression rightly seems ludicrous.

Of course, uncovering the causes of depression is important. I work with my clients to do this in psychotherapy, usually over quite a long period of time.

But unfortunately, most people who struggle with depression don’t have access or resources to do long-term psychotherapy.

And while it’s possible to discover these causes on your own or outside of a formal therapeutic context, it’s difficult. What’s more, uncovering the causes of depression is arguably the “easy” part—it’s making sustained changes to your life informed by your knowledge of the causes that are profoundly difficult.

So where does this leave us?

Probably slightly discouraged, a sentiment I feel often as a mental health professional given the complexity of the domains I work in—the intersection of cognition, emotion, behavior, culture, and society.

Still, even if uncovering the causes of depression and making structural changes to our lives and environments is beyond the scope of an article like this, I want to suggest a compatible but alternative way of thinking about the fight against depression.

While there’s a staggeringly vast number of potential causes of depression, in my experience there are two near-universal psychological factors which tend to maintain and exacerbate depression.

Addressing these maintaining factors in depression may not be sufficient to completely eliminate depression in someone’s life. But it can go a long way toward helping people understand and manage their depression more effectively.

Rumination and Avoidance: The Twin Engines of Depression

The great unintended sin of our overly-medicalized approach to depression is that it encourages people to think about it as they would an infectious disease—as though it were a malicious bacteria you’ve caught that needs to be eradicated with a strong dose of antibiotics.

But as I’ve hopefully shown above, far from a virus or bacteria, depression is often a perfectly understandable psychological response to a vast and complex set of individual-specific interpersonal, cultural, and societal stressors. If only the causes of depression were as simple as polio or influenza!

Sadly, when we train people to think of depression this way—as an infectious disease—they begin to see their own experience of depression as bad, something to be quickly eradicated, preferably via a pill.

Then, when pills inevitably fail in the long run, we turn to more subtle, but equally unhelpful, psychological attempts to eradicate the disease. And almost always, these attempts take the form of two habits: rumination and avoidance, the psychological equivalents of the proverbial “fight or flight” response.

And while these attempts to fight or run away from our depression may give relief in the short-term, they inevitably exacerbate things in the long-run.

In the rest of this article, I’m going to explain these two maintaining factors in depression and offer some thoughts for identifying them and working to lessen their influence by substituting healthier alternative habits.

What is rumination, exactly?

Rumination is the mental habit of persistent negative judgments about oneself, especially one’s perceived past failings and mistakes:

- If only I hadn’t been such a jerk, she never would have left me. I’ll never be truly lovable.

- I’m just a lazy bum. I’ve always been lazy. I’ll never amount to much anyway.

- I can’t do anything right and always screw things up eventually.

- Did I come across as rude? I shouldn’t have brought up that story about her mother. Why do I always put my foot in my mouth?

Read through just a few simple examples like these and it should be obvious how badly you’re going to feel if this is the kind of self-talk you habitually engage in, day in and day out.

The deeper question is, if we know that habitual negative self-talk and rumination like this make us feel bad about ourselves (guilty, hopeless, lonely, etc.), why do we do it? Why do we ruminate when it pretty obviously only makes our depression worse?

Part of the answer is simple conditioning. If you’ve historically associated sadness and depression with the mental habit of rumination, eventually becoming sad will automatically trigger the mental habit of rumination. In fact, this is the same process (Classical Conditioning) that Pavlov discovered with his infamous drooling dogs.

Like any habit—physical or mental—rumination can seem to “come out of nowhere” and be difficult to resist. Still, if a habit can be formed, it can also be broken.

But for deeply entrenched habits like a lifetime of rumination, breaking out of it can be difficult, especially if that habit is filling some kind of important but unmet emotional need.

In depression, for example, a common feeling is a lack of enthusiasm and motivation to do the things you know you should and want to do. In its extreme form, this lack of motivation can become what psychologist Martin Seligman termed Learned Helplessness, an almost complete despair of ever doing anything differently in the face of depression.

While many people who struggle with depression often look quite passive, it can be amazing how active their minds are—specifically, how intensely they ruminate. In fact, it could be that because they lack so much motivation to physically do anything, rumination temporarily alleviates this need to take charge of their lives and do something. Like worry in anxiety, rumination offers the illusion of control and agency in depression.

Of course, while hyper-analysis of one’s past mistakes and flaws is perhaps temporarily relieving in that it gives you something to do and feel in control of, the negative emotional side effects only contribute to one’s sense of sadness, shame, despair and apathy in the long run.

In the next section, I’ll suggest some practical ideas for breaking out of the rumination habit.

Why mindfulness is the cure for rumination

Chances are you’ve at least heard the term mindfulness before.

And while it’s typically thrown around quite casually and loosely as an apparently easy cure-all for anything that ails you, I’m going to explain why a very specific version of mindfulness can be not only helpful for dealing with rumination, but in fact, is the exact cure for it.

Fundamentally, mindfulness is the capacity to be aware without thinking. It means learning how to observe things as they are in the present moment without getting lost in thoughts about what they mean, how good or bad they are, and what happened or might happen in the past or future.

More specifically, mindfulness is the ability to control our attention—to notice when our awareness is consumed by thoughts (especially our own self-talk), and then to gently shift our attention to observing things (including our own thoughts) rather than engaging with them.

For example: You’re lying in bed and can’t seem to fall asleep. You find yourself obsessing about that awkward conversation you had on your date earlier in the evening:

- Damnit, I always put my foot in my mouth on first dates!

- Why couldn’t I have mentioned another topic? Any other topic would have been better than my last girlfriend!

- I’ll never find someone. I should just give up and accept that I’m always going to be alone.

Thoughts like these are a perfect example of rumination. It’s a kind of highly negative and judgmental (and usually irrational) storytelling about yourself. And each one of these negative thoughts generates more negative emotion (self-directed anger, sadness, hopelessness, etc.).

But how do you stop ruminating? How do you stop thinking? How do you stop storytelling?

Mindfulness is the answer.

Although we rarely recognize it, it is possible to be aware without thinking. By cultivating our attention muscle via mindfulness, we can learn to more quickly recognize when we’re caught in unhelpful rumination spirals and then disengage from those unhelpful thinking patterns by focusing our attention elsewhere.

When we practice mindfulness, we practice noticing ourselves getting sucked into thinking and then extracting our minds from that thinking back into simple observation (usually of something physical like our breathing).

For people with depression, the mental habit of rumination is strong. In a sense, it’s an addiction to a certain self-critical way of thinking.

In order to break out of that habit, we need to strengthen the competing mental muscle. We need to learn how to shift our attention and remain in observing mode without slipping back into thinking mode.

Mindfulness is the most direct and efficient way I know of to build that mental muscle and ability.

Ruminating less won’t cure your depression. But it will go a long way toward lessening your overall distress and negative emotionality. So much so that when you begin to lift the excess emotional burden of rumination, you’ll often be amazed at how much easier it is to address other aspects of your depression.

While it’s beyond the scope of this article to walk you through how to get started with mindfulness, here are three resources that can help:

- How to Start a Mindfulness Practice: A Quick Guide for Complete Beginners (Article)

- The Mindful Way Through Depression (Book)

- Sit Like a Buddha: A Pocket Guide to Meditation (Book)

Now that we’ve covered rumination, let’s move on to the second maintaining factor in depression—Avoidance.

What is avoidance, exactly?

Avoidance is the habit of turning down opportunities and experiences that are in some way difficult or scary but likely to be rewarding and worthwhile in the long-run:

- Staying on the couch watching Netflix after work because we’re exhausted rather than going for a walk or to the gym.

- Canceling brunch with a friend because we’re a little anxious and just feel “off.”

- Eating lunch in our office instead of going out to eat with colleagues.

- Turning down the invitation to join that softball league with our sister-in-law.

Of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with canceling a meetup with a friend or eating lunch in your office. In fact, being able to say no to things you genuinely don’t want to do is a key component of assertiveness.

Turning down opportunities like these become avoidance behaviors and problematic when they fit two key criteria:

- They’re habitual. We don’t just occasionally skip out on the evening walk and watch Netflix, rather, that’s the case more evenings than not.

- They’re motivated by feelings and in conflict with our values. It feels better in the short-term to stay on the couch, even though we know that walking regularly is good for our health (a value) and will actually help us feel better in the long-term.

The reason a habit of avoidance is so detrimental to us—especially when we’re depressed—is that it robs us of meaningful and rewarding experiences in favor of short-term gratification or relief. And it’s this consistent lack of meaningful and rewarding experience that maintains and even worsens depression.

When we’re depressed, it can seem like the hardest thing in the world to simply get up, get moving, interact with friends, and do some meaningful work. And yet, those are the things we need most when we’re depressed.

The challenge, then, is to figure out ways to engage with life and begin to get more of those rewarding experiences even though every bone in our body tells us we can’t, that we don’t have the energy or motivation.

Why Behavioral Activation is the cure for avoidance

You can think about depression like having an empty fuel tank. And obviously, it’s hard to go anywhere or move at all when your tank is empty, which is very often how people describe their experience of depression.

While getting a handle on your rumination habit is a good way to stop your tank from leaking and losing even more fuel, the other “half” of the problem is that you need more fuel in the first place. That’s where the concept of Behavioral Activation comes in.

Behavioral Activation sounds technical but it’s actually simple: it means doing things you find rewarding.

More specifically, behavioral activation is a structured plan for incentivizing yourself to engage in more rewarding (i.e. tank-filling) activities despite not feeling like it or having much energy/motivation.

On a superficial level, behavioral activation resembles the famous Nike motto: Just Do It.

But of course, if you’re depressed, that’s the whole problem—you don’t have the energy or motivation to do much of anything. Which is why the secret ingredient to effective behavioral activation—and what sets it apart from “Just do it”—is the concept of incrementalism.

Incrementalism is the idea that if you’re having trouble making progress on any endeavor, including engaging in more rewarding activities, the solution is to break things down into smaller steps and pieces:

- Can’t seem to actually meet a buddy for dinner and drinks? How about meeting him for lunch?

- Still too much? How about coffee for 15 minutes?

- Still too hard? Try inviting him over to watch a game.

- Still too much? Send him a text after the game about the coolest thing that happened in it.

Once you’ve found a small enough increment, do it until you begin to notice a small uptick in motivation and energy. Then, go for the next smallest thing on the list. Rinse and repeat.

I had an old supervisor who used to say:

I’ve never seen someone so depressed that they couldn’t go to the bathroom. If they can find the energy to get into the restroom, that’s a start, something we can build on.

The key to breaking the cycle of avoidance, then, is to combine behavioral activation—a structured plan for doing things that are personally meaningful and rewarding—with incrementalism in order to get over the motivation problem.

In fact, the most powerful effect of incremental behavioral activation is to chip away at the belief that because I don’t feel motivated, I can’t do anything.

By showing ourselves experientially—in very small ways at first—that that belief isn’t entirely true, we can guide ourselves to ever-increasing levels of activation and therefore reward. We can start to re-fill the tank.

Perhaps most importantly, in the long-run, we can construct a new belief about the very nature of motivation itself: Yes, motivation helps me do difficult things, but doing difficult (and rewarding things) actually leads to more motivation. In other words, we build a more sophisticated model of motivation and action, one that is bi-directional.

All You Need To Know

Let’s review: There’s an important distinction between the causes of depression and maintaining factors in depression. While the causes of depression are often highly diverse and individual-specific, there are two nearly-universal factors that maintain it:

- Rumination is the mental habit of persistent negative judgments about oneself, especially one’s perceived past failings and mistakes. To undo this habit, mindfulness is the best solution since it helps cultivate the ability to shift our attention away from ruminative thinking and instead move toward non-judgmental awareness and acceptance.

- Avoidance is the habit of turning down opportunities and experiences that are in some way difficult or scary but likely to be ultimately rewarding and worthwhile. The key to breaking free from avoidance cycles and re-engaging with life is to use incremental Behavioral Activation to dispel the false belief that we need to feel motivated in order to do important things.

For most people struggling with depression, identifying and addressing the structural, interpersonal, and biological causes of their depression is necessary at some point in order to truly undo the grip of depression. But no matter what those causes are, anyone who struggles with depression can learn to undo the habits that are making it worse.

Depression feeds on rumination and avoidance. Starve it of these energy sources, and you just may turn the tide on your war with depression.

26 Comments

Add YoursI enjoy your analysis and appreciate your relatively evenhanded approach to both behavior and pharmaceuticals. Behavior modification is an always to me and pharmacological is intervention is something that should be used as an adjuvant depending on need. Not the other way around

Thanks, Andrew! That’s really well put!

I have been dealing with crippling depression for the past year almost. I was always someone who was very negative and I had been on various SSRIs and benzos since I was a teenager. I didn’t know real depression until recently though. I wasn’t depressed back then. Most people being treated probably aren’t either but that’s something else entirely.

You described my personal life and mental state in detail that gave me chills. I spent days on end, in a dark room, alone, talking to myself in my head asking myself all the questions you used as examples. I stopped talking and seeing everyone in my life. I avoid human contact to such an extent that I’ll turn off my phone because a text message seems intrusive.

I see the vicious cycle you describe. I am sad because my life didn’t turn out as I planned so rather than trying to fix it I just dwell on my past failure and then my life gets worse so I dwell on it more and…

I am sad so I chose to skip a birthday party to stay home watching movies. I ignore invitations to meet up with friends because I’m bummed out but then I get even more bummed out that I don’t have any friends and I’m alone. My list of friends slowly dwindled down to no one and every time I ditched a friend I got more depressed and then was less likely to see someone in the future.

It’s like how my messy living area depresses me but it just leads to me letting my living area deteriorate further.

When things got really bad and they put me on 8 meds at one point, it did more harm than good because it made me feel justified in my depressed state and have me terrible side effects that we’re an excuse to feel sorry for myself.

This article has given me a lot to think about. Well, it really gave me a lot of things to stop thinking about.

Your mentor never saw anyone too depressed to go to the bathroom? I don’t think you are truly depressed if you never spent multiple days on a couch without food or water smelling like a truck stop bathroom unsure if you pissed yourself if you are so dehydrated that your body isn’t producing any urine.

I’m rambling. This comment makes no sense but what you should take away is that this article helped me.

Thanks for the thoughtful reply, Henry. Glad the article was useful.

A man that knows to paint the invisibles while adding his flair of personal experiences and hard earned wisdom. Unleashing a craft that embody a fragment of our internal life that allows us to reflect, co-create, and a license to evolve beyond our limiting senses and perception by embracing such masterpiece. Thank you for the enlightenment. Now I’m empowered.

Thank you, Kaizen.

Same good ol’psychobabble. Years and years, a little rehash, but same ol’stuff.

Why not say the Savior truly has all the answers, it may not line your pockets as handsomely but it will help people get their noses into the Book!

The savior! oh Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse. Get real . Are you describing avoidance? Yes you are. Not helpful your comments. We are serious here. Talking about life changing and peace.

I was under the impression that Rumination and Avoidance are symptoms of depression.

After reading this article I’m still not sure what makes you believe they are causes.

It’s one of the unique challenges in mental health that the relationship between symptom and cause/contributor is often bi-directional.

If you look back, you’ll see that nowhere in the article does it say rumination and avoidance cause depression. The author posits rumination and avoidance maintain depression. There are endless, multifaceted and dynamic causes of depression — also stated above !

Right!

What an amazing article! I seen myself so many times throughout. I’ve had major depression most of my life,with not much help from antidepressants,and or therapy. Thank you for a different outlook, that I’ve never read before.

You bet, Michelle! Thanks for the kind words 🙂

–Nick

Depression, for me, was from just too many life traumas and struggles that were too many and too hard. No room or need for details here. I was victimized as a child by a horribly narcissistic and abusive parent, and later by spouses. At nine, father gone after divorce, there was no protection. I was “trained” to remain a victim. Overcoming depression has been a combination of medicine (no longer needed,) therapy (“reparenting” by an exceptional therapist brought me to understand there can actually be people who value and care about me,) and almost accidentally learning, on my own, to do a “thought-stopping” mindfulness. I just happened to read a little article about how ingrained thinking creates rumination superhighways in the brain synapses. Your simple answers are wonderful. However, there are sometimes larger issues than negative self image. Sometimes the problem is much bigger and requires more and varied solutions. Sometimes one’s whole world view needs rearranging and with help.

Completely agree about the bigger issues, Eileen, which is why I spent the first part of the article talking about the complexity of what causes depression. My point was simply to show that often focusing on reducing rumination and avoidance can help for many people.

Cheers,

–Nick

Wow. Right on. I will pass this on to my psychologist (she seems to be on right track …) and my psychiatrist (who getting on the right track) who is support my decision to get off of SSRI’s. Thanks, I keep in touch. Mark G.

Thank you so much! You’ve helped me focus on the present and move forward.

Maybe the single best piece on Anxiety and Depression that I’ve ever read. On second thought, the single best piece I’ve ever read. Well done, Nick.

Brilliant! Very good, practical information that can be applied to and used in our everyday life in order to compete with the endless supply of depression grog that seems to reside in our brains. Thank you, Nick. My life is better for having you in it!

Great article with real-life solutions that anyone can benefit from. I thought the ‘avoidance’ was going to be along the lines of avoiding feelings (which is a whole other issue I’m working on). Always trying to improve myself and my emotional intelligence.

I am glad this older article came back around. It is both simple, actionable and insightful. I have shared with several family members who struggle with anxiety or depression. So important for people, despite not having the whole answer, to have specific ways to address as many of the peripheral and add-on issues as possible. It is harder the deeper the depression is for sure.

I hope the earlier poster is doing well. If you read this, Henry Lukas, let us know how it is going.

I will need to re-read his article. *My avoidance is in a way, a holiday. I kept up the pace all week tending responsibilities. The job, the teaching, the workshop, the bills, the animals, the Oh Spring? The seedlings. Today, though, is a do-nothing day.

My schedule is clear. No guilts to kick back. I wonder often if I am depressed, or truly, just fine in my weekly day off. May I encourage others to try this? It has been built into my schedule over 30 years.

So glad I found your article, Nick. I hope to follow your articles and continue reading of your thoughts.

Nick,

Been reading your content for some time now, and I find it so very helpful. I would like to pass along a book I just read that might compliment this artical as far as “activating” goes. It is “Solving the procrastination puzzle” by Timothy A. Pychyl, PH.D

Thank you Nick

This helped me have a better perspective and a place to start to hopefully feel better.

I agree with you and appreciate the well written reminder.

You have a gift – thank you for sharing it

Thank you Nick

This helped me have a better perspective and a place to start to hopefully feel better.

I agree with you and appreciate the well written reminder.

You have a gift – thank you for sharing it