Imagine you’re driving home from work… and then, out of nowhere, a red sports car zooms by and cuts you off.

You’re immediately angry and thinking to yourself:

What a jerk… he ’s gonna kill somebody driving around like that!

In this situation, what caused your anger?

While it’s tempting to say the jerk in the other car caused you to be angry, that’s not quite right. While the sports car (and its driver) was the trigger for how you felt, it was your interpretation of what that trigger means that caused your anger. In other words, it’s your story about the trigger, not the trigger itself, that caused you to feel angry.

Think about it this way:

- What if you knew that the person driving the red sports car was your brother-in-law and that your sister was in the passenger seat going into active labor, so that the reason they were speeding was to get to the hospital quickly? I bet that would change how you felt.

- Or, what if your first reaction to the sports car zooming by you was to look down at your speedometer and realize that you were only going 45 miles an hour in the fast-lane? Your emotional reaction might be closer to guilt or embarrassment than anger.

In all three cases, the actual events were the same—you got cut off while driving—but your emotional reaction was completely different depending on your thoughts about the event and what it means.

That’s cognitive mediation. And it’s one of the most important ideas in all of human psychology.

In the rest of this essay, I’ll explain how cognitive mediation works and how you can use it to improve your emotional health, resilience, and peace of mind.

What Is Cognitive Mediation Theory?

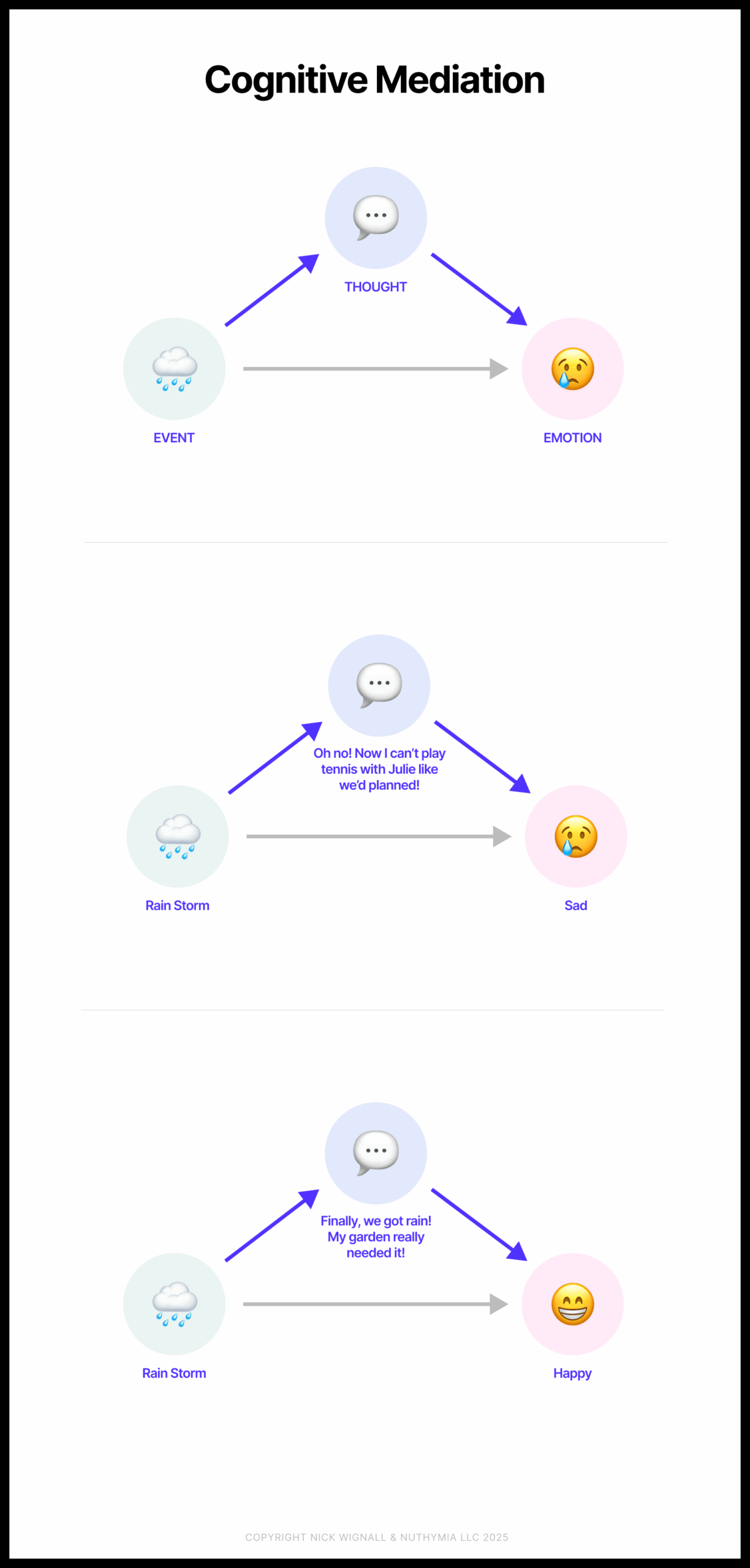

Cognitive mediation theory is the psychological principle that events don’t cause emotions; rather, it’s our thoughts or interpretations of what the events mean that cause emotions.

For example:

- Rain doesn’t cause disappointment; it’s the story you tell yourself—because it’s raining I can’t play tennis with Julie—that leads to disappointment.

- For another person, that exact same rain shower triggers a different story—it’s wonderful that my garden is finally getting some rain!—which leads to a different emotional reaction like relief or joy.

Cognitive mediation was codified into a psychological theory in the 1970s by Richard Lazarus. But it’s actually a very old idea that’s been expressed by nearly all of the major wisdom and philosophical traditions from buddhism to stoicism.

My favorite version of cognitive mediation comes from Marcus Aurelias in his Meditations:

The soul becomes dyed with the color of its thoughts.

Put a little less poetically:

Things don’t cause emotions. It’s your thoughts about things that determine how you feel.

This simple idea turns out to be profoundly important when it comes to our emotional health and wellbeing.

To see why, I’m going to walk you through a handful of very common examples of cognitive mediation and its effect on our emotional lives.

Examples of Cognitive Mediation

Cognitive Mediation shows up everywhere. But because it happens in our heads, being aware of it happening—especially in real-time—can be difficult.

To help you understand what cognitive mediation is—and also to get better at noticing it in your own life—I’ll briefly explain the main types or forms it takes and then illustrate some of the most common examples of it I see in my work as a psychologist.

There are 3 major types of cognitive mediation:

- Self-Talk. The voice inside your head narrating what happens in your life. Some of the most common unhelpful versions of self-talk include worry, rumination, and self-criticism.

- Expectations. These are stories you tell yourself about how things should be. They typically take the form of should statements—“He should be more respectful!” or if-only statements —“If only she were more affectionate we wouldn’t argue so much.”

- Beliefs. Beliefs are relatively enduring convictions about the truth of things. For example: “The world is round; Coke is better than Pepsi; I’m not creative; Everything is always hard for me.” Limiting beliefs are beliefs we hold that limit or hurt us, and are typically exaggerated or extreme in nature.

To make things even more real, here are a few of the most common examples of unhelpful or negative cognitive mediation that I see with my clients….

Worry Mediates Anxiety

Worry is unhelpful negative thinking about the future. And it’s the only direct cause of anxiety.

For example:

- Your kid riding a bike without training wheels for the first time doesn’t cause anxiety. It’s you worrying about them falling off or getting hurt or not enjoying it that causes you to feel anxious.

- Your coworker looking at you during a meeting doesn’t cause you to feel anxious. It’s you worrying about what that look means—He thinks I don’t know what I’m talking about—that causes your anxiety.

- Getting in bed at 10:30 rather than your usual 9:30 bedtime doesn’t cause you to have sleep anxiety. It’s worrying about the fact that you got into bed too late that leads to the sleep anxiety.

Now, there are plenty of other factors that can indirectly influence your anxiety—everything from hormonal fluctuations to how much sleep you got last night. But those factors don’t directly cause anxiety. They might predispose you to be more or less anxious and make you more or less vulnerable to anxiety. But it’s possible to have all those things happen and not be anxious if you avoid worrying.

If you want to learn more about cognitive mediation and the relationship between worry and anxiety specifically, check out this article of mine: Worry Is the Engine of Anxiety →

Rumination Mediates Anger and Resentment

Rumination is unhelpful negative thinking about the past. It often takes the form of dwelling on the faults and failures of others and how they may have hurt you.

For example:

- Your spouse’s sarcastic comment doesn’t cause you to be angry. It’s your thought about what that comment means—Why does he have to be such a jerk?!—that causes your anger.

- Your father not being affectionate enough when you were a child isn’t causing you to be angry right now. It’s the fact that you’re dwelling on memories of your childhood that’s causing you to feel angry and resentful.

- Your teenage son leaving his dirty clothes on the floor after the third time asking him to pick up doesn’t cause you to feel impatient or angry. It’s the story you tell yourself about how disrespectful it is that your son doesn’t listen that causes your anger.

It’s very common to fall into a pattern of thinking where we blame other people for how we feel. And while other people may very well have done or be actively doing bad, mean, or disrespectful things, that doesn’t mean they are responsible for how we feel.

You are responsible for your actions, not other people’s feelings. Similarly, other people are responsible for their actions, not your feelings.

If you want to learn more, here are a couple articles on the topic of anger and resentment that might be helpful:

Envy Mediates Jealousy

Envy is unhelpful negative thinking that compares what you lack with what others have. And it’s envious thinking that causes the emotion of jealousy.

For example:

- Your coworker getting a promotion and raise doesn’t cause you to feel jealous. It’s thinking enviously about how she’s now more senior than you in the organization even though you’re smarter and harder working.

- Your best friend getting engaged doesn’t cause you to feel jealous. It’s envying them for their “luck” at finding a great partner that causes the jealousy.

- Your son getting accepted to an Ivy League school doesn’t cause jealousy. It’s the story you tell yourself about how unfair it was that Dartmouth rejected you and that you were just as accomplished as your son that leads to the jealousy.

For a more detailed breakdown of the difference between jealousy and envy, I wrote a piece on the topic that might be helpful: Jealousy vs Envy: How They’re Different and Why It Matters →

Self-Criticism Mediates Shame

Self-criticism is unhelpful negative thinking about your faults, failures, or deficits. And it’s the habit of thinking self-critically that leads to the feeling of shame.

For example:

- Botching a presentation at work doesn’t cause you to feel ashamed. It’s the story you tell yourself about what that failure means—I knew I shouldn’t have volunteered to take on this project… I’m not good enough to do this—that causes the shame.

- Sneaking junk food late at night doesn’t produce shame. It’s the thoughts about what your spouse would think about you if they knew you did it that produces the shame.

- Your mother criticizing your schoolwork as a kid doesn’t cause shame. The story you tell yourself about how you’re not actually very smart is what causes you to feel ashamed.

Keep in mind, cognitive mediation doesn’t detract from the negativity—either moral or psychological—of what happens or has happened to you. It just highlights how those events don’t determine your emotional reaction.

In the final section we’ll explore this more closely and see how cognitive mediation is ultimately a profound source of psychological freedom and empowerment.

Why Cognitive Mediation Matters for Emotional Health and Resilience

Cognitive mediation matters for two main reasons:

- It’s a more accurate explanation of how the mind works.

- It’s a more helpful and pragmatic way to live your life.

Of course, on one level it’s appealing to believe that things cause emotions. If you believe your emotions are the result of external factors, then you’re not responsible for your emotions—how you feel is up to other people, chance occurrences, even fate. And this can feel superficially relieving. But long-term, viewing external events as the cause of your emotions is profoundly disempowering and typically leads to feelings of chronic helplessness, victimization, and cynicism.

On the other hand, if you believe emotions are the result of internal factors, it’s initially going to be more challenging because you’re claiming responsibility for your emotional life and can’t blame anyone or anything else for how you feel. But long-term, you’re going to feel much more confident, empowered, and optimistic.

But your belief in cognitive mediation as an explanation for your emotional life doesn’t just affect how you feel—important as that is. Eventually it will affect your behavior— your habits, your core beliefs, and even your identity.

For example:

- Suppose you feel chronically anxious and insecure at work… If you believe your anxiety and insecurity is the result of other people devaluing you, or being born with an unlucky set of genes, you’ll be less motivated to make positive change because other people and your genetics are not something you can affect anyway. On the other hand, if you believe that your anxiety is the direct result of your habit of worrying—especially worrying about what other people think—because that is something you can control, you’ll be more likely to take steps to break your worry habit so you can feel less anxious.

- Or let’s say you’re angry about the state of politics in your country… If you believe other people are responsible for your anger, you’ll be less motivated to change because fundamentally you can’t change other people and you’re just stuck with what you’ve got. But if you believe that your anger is the direct result of your habit of ruminating—especially ruminating about what idiots all those people in the other party are—you’ll be more likely to tone down the ruminating (because it’s something you can control) and instead, start doing something productive—volunteering, educating, maybe even running for office yourself.

Cognitive mediation is about taking radical responsibility for your emotional life.

Because the more you own your emotions—the more emotional agency you have—the more effective you will be at managing difficult circumstances in life well and developing ever greater degrees of emotional confidence and resilience.

We can only change what we can control. And while you can’t change emotions themselves, if you can learn to notice and take responsibility for the mental habits that generate them, you’ll have far more positive control over your emotional life than you ever thought possible.

How to Use Cognitive Mediation to Be More Resilient

Here’s the basic argument of this essay:

- How we feel emotionally comes most directly from how we think.

- So feeling intensely or excessively negative is the result of thinking in an intensely or excessively negative way.

- The implication is that you can change how you feel—including feeling less emotionally overwhelmed or upset—by building better habits of thought.

Habits of thought?

We all know that our physical habits play a crucial role in our physical health…

- The quality and quantity of food you’re in the habit of eating will have a critical effect on your metabolic health.

- The quality of your sleep habits will play a big role in the quality of your sleep and energy levels.

- The quality of your physical activity and exercise will have a large effect on your strength and endurance.

Similarly, our mental habits play a critical role in our emotional health…

- Whether you’re in the habit of responding to your worries with more worrying or redirecting your attention elsewhere will have a huge impact on your anxiety levels.

- Whether you’re in the habit of criticizing yourself for feeling bad or being compassionate with yourself will play a large role in how vulnerable you are to depression.

- Whether you’re in the habit of ruminating on errors and mistakes vs using them as opportunities for learning and growth will play a large role in how optimistic and positive you tend to feel vs cynical and negative.

These invisible habits of mind are the main levers we have to influence how we feel emotionally and how we respond to challenges and stress. But you’ll never see them as levers you can pull and adjust if you think of your emotions as being caused by external events.

Embracing cognitive mediation increases both your awareness of and agency over the mental habits that largely determine your emotional experience.

So, if there’s a particular emotion you struggle with—whether it’s anxiety, shame, anger, or regret—here’s a simple way to use cognitive mediation to improve things:

- Keep track of which events trigger that emotion. For example, if you struggle with anger, keep track of which events or situations are most likely to trigger feelings of anger in you.

- Once you’ve done this for a week or two, you’ll start to notice patterns. Specifically, there are probably a handful of events or situations that predictably trigger that difficult emotion.

- Now, use that trigger as a cue to reflect on what mental habits come up in between the trigger and your emotion. In other words, what’s the story I’m telling myself about this trigger?

- As you expand your awareness of the cognitive habits mediating the triggers and your emotions, start to get curious about the nature of those stories: How accurate is the story I’m telling myself? How helpful is it? Are there other stories I could tell myself? Do I have to tell a story at all?

Ultimately, cognitive mediation shows us that we have quite a bit of agency and control over our emotional lives. And while exerting agency and healthy control isn’t always easy, it is possible.

As the great Viktor Frankl put it:

Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.

Sometimes that response is a physical behavior. But it’s just as likely to be a mental behavior—a story we tell ourselves.

I’ll wrap this essay up with a final thought and question for you to consider:

The quality of our lives depends on the stories we tell ourselves.

What kind of a storyteller are you?

Next Steps

If you’re interested in learning more about making positive changes to your emotional health, here are a few ways I can help: